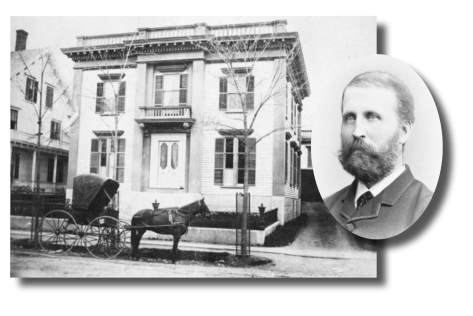

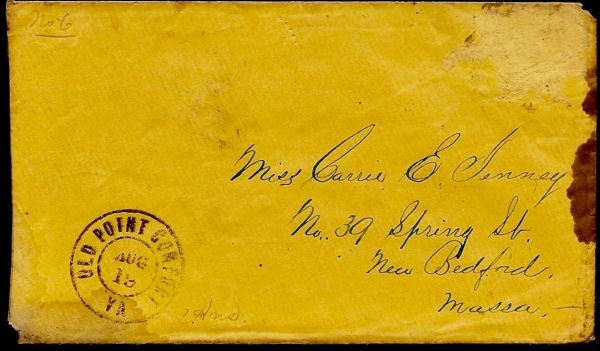

I’ve titled this small collection the “Miss Carrie Jenney Letters” because all of them were either addressed to—or forwarded to—Miss Carrie Jenney of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) and Caroline Brownell (1823-1855). She most certainly was the one who preserved the letters. In the 1860 U. S. Census, five years after her mother’s passing, we find Carrie enumerated in the household of her grandparents, Joseph Brownell and Lydia Almy. She later married Alfred Wells Case (1840-1908), a paper manufacturing magnate and lived comfortably in Manchester, Connecticut.

Most of the letters were written by her kin and pertain to a trip taken by her uncle, Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell (1842-1901)—who was only five years her senior and about to enter his Senior year at Harvard—and her aunt Josephine’s husband, Dr. Irah Eaton Chase, an 1850 graduate of Wesleyan University, an 1852 graduate of the Berkshire Medical Institution, and a practicing physician in Haverhill, Massachusetts. The trip from Massachusetts took them through Philadelphia where Frank and the Dr. were made delegates of the U. S. Christian Commission (USCC) and given a five-week assignment to serve at a USCC station located five miles from City Point at the 18th Army Corps field hospital in front of Petersburg in August 1864. Their arrival there, just after the failed Battle of the Crater, during the Ammunition Barge explosion at City Point, the Second Battle of Deep Bottom, the taking of the Weldon Railroad, and the start of construction of the Dutch Gap Canal, provided the two men an unusual opportunity to observe and write of events from the rare, unbridled perspective of civilians free to move around.

While Frank and Dr. Case were on this trip, we learn that the Dr.’s wife—Josephine—and another younger woman named Fanny, most likely also a relative, were using the occasion to serve as nurses at the Mount Pleasant Hospital in Washington. Their observations are equally intriguing.

Letter 1

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his older sister, Almira Emily (“Emma” or “Em”) (Brownell) Cummings (1834-1915), the wife of Charles Smith Cummings (1830-1906) of New Bedford, Bristol county, Massachusetts.

Wednesday, August 3rd 1864

Dear Em[ily Cummings],

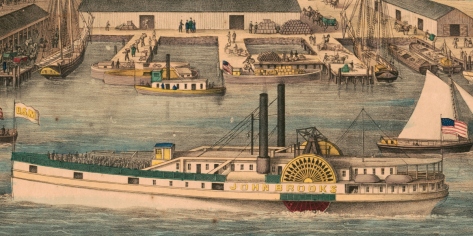

Now I am on board the U. S. Mail boat “John Brooks” steaming up the James river about 20 miles from Fortress Monroe. I suppose you know all about our adventures till the time Dr. and I left Washington from previous letters of Jo[sie], Fannie, and myself, written home, for I suppose they are read by all. I will begin then where they left off.

We started yesterday from Washington at 2 o’clock. My outfit was as follows. On my left side was my canteen, filled with water and enough tea to give it a flavor. Sometimes they put in essence of ginger and sugar—in fact, anything to give it a taste, and make it quench the thirst better. On the other side was my haversack, also strapped over the shoulder in which was crammed everything I thought I should need. In my hands I carried the “set” for my future sleeping apartments—a rubber blanket and an army one, rolled up and strapped together. I was clothed in corduroys, collarless flannel shirt, old hat, and looked decidedly rough. There are six of us in the party. The boat is full of army officers and a negro company. These last made any amount of fun with a fiddle they had—such jigs and breakdowns would shame Morris Bros. We find now that we are under martial law. About once in five minutes chaps come round and want to see our passes, which proceeding is getting to be rather of a bore.

The sail down the Potomac was very beautiful. On both sides are seen forts and earthworks and the river itself is full of steam vessels of all sizes and kinds. We stared at Mt. Vernon as we passed and also imagined we saw Fairfax Academy in the distance. Whether the red spot we saw was that identical building depends upon the veracity of a chap that pretended to know. The arrangements aboard are exceedingly primitive. To sleep we spread our blankets on the deck, took haversacks for pillows, and snoozed. My bones don’t ache this morning half as much as I expected but all my endeavors to find a soft place were in vain.

We stopped at Fortress Monroe this morning at 5 for 5 hours. Now I always thought this was a sort of a wilderness down here but you ought to have seen the jolly breakfast we had—steak, coffee, jelly, condensed milk, &c. &c. &c. Then we loafed around on the shore for awhile. Now, to digress, some people always like to lay away relics from every place they go to and I must admit I crammed one of my vest pockets with pebbles and shells, but what to do with the things now I have got them, I don’t know. Guess I will throw them away. If anybody wants to see anything that is from Fortress Monroe, I propose to show them my left foot and say, “Behold, that foot I brought all the way from Fortress Monroe.” If you have a failing for “furrin” relics, a glass case will preserve this scribble written on my knee.

Then we went into the fort, saw the largest gun in the world, 15 inch, sends 600 lb. ball and weighs 32,000. ¹ Come down and we will show it to you. The parapet is nearly a mile around. Between 400 and 500 guns. Lying off the fort were any amount of vessels—two gunboats, English man-of-war, French man-of-war, the frigates Minnesota and many others. Starting away at 10 we saw the wreck of the Cumberland, the scene of the fight between the Monitor and the Merrimack, Hampton, and Old Point Comfort. These are things I never expected to see. This brings me down to the present.

Sand[ford] Olney has returned from the front and is stationed near Washington for his remaining 20 days of service. Heard of him in town but did not see him. Josie will let him know she is in town and probably see him.

I met in Washington quite a number that I knew—among them two classmates. Called on Elisha Gerrish from New Bedford. Dr. fell in with some Haverhill people. Jo will write all the news from that department. I have not found it so hot as I expected except when in Washington and then it was a remarkably hot day everywhere. Shall get to City Point at 5 this afternoon. Like it first rate thus far. Shall stay three weeks. Let them all see this at the house as I shall begin my next letter to Carrie where this leaves off. I want everyone of my letters answered. Haven’t heard from home since I started. Love to babies.

— Frank

¹ Soldiers often referred to this weapon as “the Lincoln Gun.” Harpers Weekly called it “the Biggest Gun in the World” in the March 30 1861 edition.

Letter 2

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his niece, Miss Carrie Jenney. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Before Petersburg

Sunday, August 7th 1864

Dear Carrie,

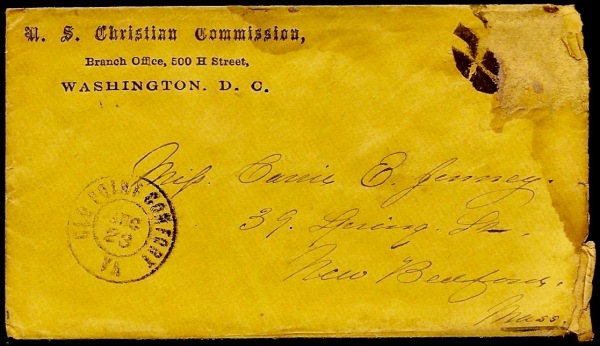

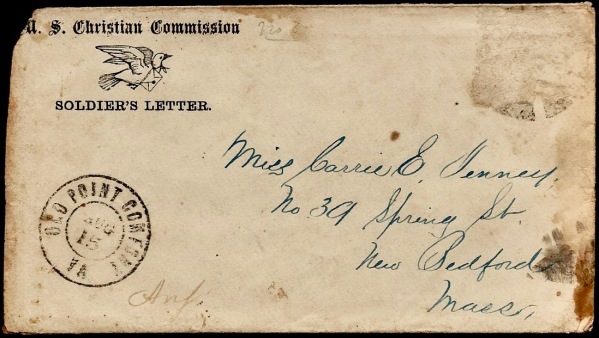

My last was written from Washington and beginning from that time I wrote to Em while coming up the James River. You will have to read hers to keep the connection. I suppose you will find this the third letter I have written to you since I started. Maybe you have not got them all. One thing I am certain of—that although I have written seven since I left, not one have I got. But I suppose that there must be lots on the way. I expect a separate answer to every one of my letters and that daily journal. Direct to “No. 500 H Street, Washington D. C.” as before. ¹

As we approached City Point—the base of Grant’s present campaign—we passed Wilson’s Landing, Harrison’s Landing, Fort Powhattan; all scenes of some military operations. Did you ever know why it is called Harrison’s Landing where McClellan embarked? Here it is. The old homestead of Gen. Harrison is near and thence the name. Stared at the homestead and took a note.

Above City Point about a mile or two is Bermuda Hundred where Butler is in command. I suppose it would be impossible for me to give you so good an idea of what City Point is in writing as I could in word so I will reserve that till I get home. But I can tell you what my first idea of a camp was from the view I got from the side of the covered cart I rode up to my present station in. And from the view I got, I shall proceed as follows: With raw material to make a military camp, take an irregularly shaped piece of the country about ten miles long and two miles wide, about half woodland, burn two-thirds of said woodlands, and leave blackened stumps. Then throw in any amount of dirty tents, mules, enormous meat carts, contrabands, and flies. There’s your camp. To make the semblance still better, harness to each of the covered meat carts six mules, put a contraband on the pole one, and arrange them in strings of twenty or more each. Let them go in every direction and these will be “army trains.” Have a lot of solitary horsemen riding to kill in every side, and finally make everything dusty, hot, and disagreeable. Pitch the tents in squads here and there and the picture will be complete. But you must remember that this applies more strictly to the portion of the field to the right wing near the base of operations [at] City Point and the nearer to that, the more mules, flies, and confusion. But the farther you go in the other direction, the less men you see.

It’s odd but here are two armies of perhaps 100,000 each and they do not see each other. A man that shows his head above the ridges or ramparts on either side gets popped by a sharpshooter. Everybody keeps out of sight behind batteries and in rifle pits, or way in the rear.

I will tell you where I am and close. I am sitting on my bed writing on my knee from the U. S. C. C. [U. S. Christian Commission] tent at the 18th [Army] Corps Hospital. This hospital has about 1200 in it. While I am writing, about 200 are coming in from the extreme front. Lots of sick folks in this family. Think of it—twelve died last Wednesday night and every night at sundown there is a squad that goes out and buries those who have died since the previous sunset.

As for me, like a fool, I worked too hard the first day and a half and had to give up all—used up. Rested three days and now am getting alright again. Shall take things easy in future.

Tell Father to set Kelligrew on my second pair of boots. The first pair of thin ones I suppose are done. Let him start on the thick ones so as to have them done when I get home. — Frank

Do not be surprised if you don’t get another letter in a week for the mails between City Point and New Bedford are somewhat irregular. Shall write day after tomorrow.

¹ 500 H Street in Washington D. C. was the Branch Office address of Rev. S. L. Bowles, Local Agent of the U. S. Christian Commission in 1864.

Letter 3

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his niece, Miss Carrie Jenney. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Before Petersburg

Thursday, August 11 [1864]

My Dear Carrie,

Yesterday I wrote to Em and today is your chance. Last night—or rather day before yesterday—I received your letter No. 2. The first one that you wrote, I did not get nor have any papers appeared. It seems too that you did not get my first letter written in Philadelphia. Perhaps that is on its way. This, I think, is my fourth letter addressed to you, so you can tell whether you get them all. By the same mail, I send a note to Father.

I suppose that before this you have seen in the papers accounts of the terrible excursion—no! not exactly that; I mean explosion—that happened at City Point day before yesterday. ¹ We heard the noise and everybody rushed from the tent to see what was the matter. I thought Grant had been trying to blow up another battery. ² It was, however, in the opposite direction in our rear and we could see the immense volume of smoke arising. Hearing during the afternoon of the nature of the disaster, I went down to see—it is five miles off, you must know. The scene was but a repetition of that at Lawrence when the Pemberton Mill fell in [1860]. In every direction were lying remnants of guns, ammunition stores, fragments of exploded shells, mixed with pieces of building. The bodies had been collected and were lying in rows. Portions too small to be called men [such] as legs, arms, &c. were put together in bags. How many were killed no one knows. But what puzzles me is how the keel of the barge—on which the explosion—was thrown 60 feet into the air and landed on a bluff.

Here nothing of much interest has occurred in the field. Night before last we had heavy firing nearly all night and it was kept up at intervals during the whole day. Today and this evening all is remarkably quiet. Usually at sundown they begin to bang with the guns and bellow with the mortars. They keep up this innocent amusement till about ten o’clock when the firing gradually dies away. Today they have been practicing with some Greek fire or something similar in our camp but not against the enemy—merely experimenting; perhaps for future use.

Grant is up to some other dodge since his last failed so badly, for several thousand men have been called on for special duty for twenty days with extra pay. More digging I guess. ³

As it is getting late and everybody else is in bed but myself, I guess I will join the majority and take a little snooze myself. Am all over with my little sickness and anticipate no future trouble. — T. Frank

¹ In an act of sabotage, Confederate Secret Service Agent John Maxwell smuggled a bomb onto a barge loaded with ammunition as it sat tied up to the wharf at City Point. The explosion detonated 30,000 artillery shells and 75,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. At least 43 people were killed instantly and 126 were wounded. The wharf was almost entirely destroyed and the damage was put at $2 million.

² A reference to the Battle of the Crater which took place only a week earlier.

³ Probably a reference to the Dutch Gap Canal, most of which was by the labor of United Stated Colored Troops (USCT).

Letter 4

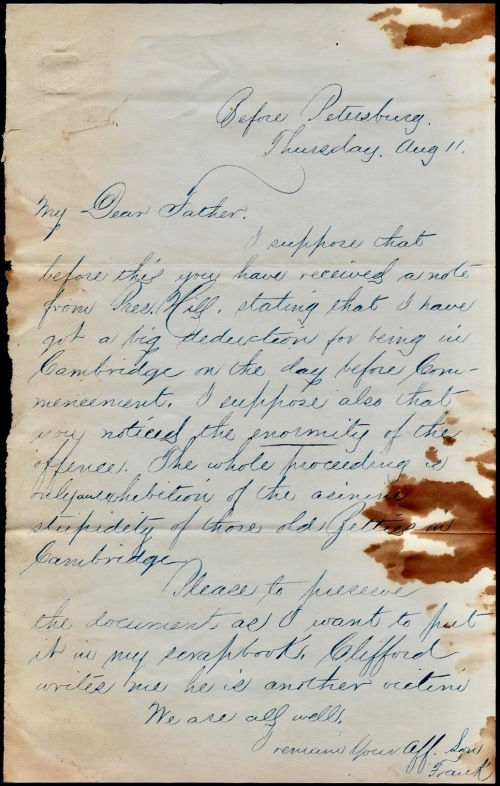

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his father, Joseph Brownell (b. 1795).

Before Petersburg

Thursday, August 11 [1864]

My Dear Father,

I suppose that before this you have received a note from President [Thomas] Hill stating that I have got a big deduction for being in Cambridge on the day before commencement. I suppose also that you noticed the enormity of the offense. The whole proceeding is only an exhibition of the asinine stupidity of those old Betties in Cambridge.

Please to preserve the document as I want to put it in my scrapbook. [Charles Warren] Clifford writes me he is another victim. We are all well. I remain your affectionate son, — Frank

Letter 5

This letter was written by Josephine (“Jo” or “Josie”) (Brownell) Chase (1836-1898) to her niece, Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Josephine was married to Dr. Ira Eaton Chase (1831-1919) of Haverhill, Massachusetts. Dr. Chase is the “Dr.” who accompanied T. Frank Brownell to City Point, Virginia, for a five-week stint with the U. S. Christian Commission. We learn from the letter that she and Fanny were working as nurses at the Mount Pleasant Hospital in Washington.

Washington

[Sunday] August 14th 1864

Dear Carrie,

I shall have to give you a scolding if you don’t do better. I have written to you five times and have only heard from home once. Fannie received a letter from Emily on Friday and on the envelope was written something to this effect—that you have written again—so I am hoping there is a letter for me somewhere on the road. We hear from Frank [Brownell] and Dr. [Ira E. Chase] often. They seem to be getting along very well. Doctor says it is “gloriously rough.” I suppose the papers from Haverhill arrive safely at No. 39. Dr. writes over *** and ordered copies to be sent to Father.

I hardly know what to write about. I have almost forgotten what I have already written to you. I think I told you that we were stationed at the Mt. Pleasant Hospital. In my ward, there are sixteen or eighteen men—two of them sick with fever, three with chronic diarrhea, one with rheumatism, one wounded in groin, two in head, two with arms off [and] the rest with amputated legs. Two went home on furlough last week. Three are going this week. We of course feel most interested in our particular wards but we have access to all the men in the hospital.

We went into the gangrene ward the other day to see if we could do anything for them. Poor fellows. I pity them. I think the air was more impure than any place we have been in. We don’t mind it very much after we have been in a few minutes.

The “boys” are not getting along very well. It is so hot this week. Such quantities of flies I never saw. Some of the boys faces as well as bodies are literally covered. They have have a fan to keep them off but some are so weak they soon get tired. Each one ought to have someone to sit right down by their bedside and attend all of the time to them. It seems as if we could not do anything for them—there is so much to be done.

The “regular” nurses I don’t know what to think of. We went into a ward the other day and one was sitting and rocking away hemming ruffling. In our hospital we have not seen them doing one thing for the soldiers. We meet them occasionally walking through the halls trying to fan themselves and keep cool.

I never knew that it could be so hot as we have had it here. The last thing I know of, at night, Fannie is about half asleep, fanning away until she gets to sleep. We wake in the morning as warm as when we go to bed. The perspiration will stand in drops on our hands just while we are lying perfectly quiet on the bed. You can imagine what it would be when we are exercising. We usually leave home in the morning at nine and get back any time before five. Saturday we did not go until after dinner as we had ten stand-cloths to hem for Fannie’s ward. They were anxious to have them by Sunday because the Surgeon General visits the wards on Sunday for general inspection and they liked to look pretty well.

When we were about to return from the hospital it commenced to sprinkle and by the time we arrived at the horse-car we were having a severe tempest. Just after we entered the car, such a crash! It seemed as if the car was struck, but just then, turning my head, I saw a cow just the other side of the fence was struck. She fell dead instantly. It gave us a real start. We were never so near danger before. The soldiers in the car said it sounded like a shell. I never want to hear one if it sounds like that.

We are both real well and have voracious appetites. Write real often and great long letters too. Much love to all. — Josie

I suppose Frank writes to you often. Miss Forden [?] is at Armory Square. We shall call on her the next time we go there. Sanford [Olney] calls to see us often. His time will soon be up.

[Washington]

Sunday P. M. [August 14, 1864]

My dear Carrie,

It seems good to talk with those at home with our pens now we are so far away. I should not enjoy being here alone unless I could stay all the time in the hospital and Josey and I think New England is the place to live in. We rush about together and laugh over our trials and talk about our sick men and visit them together and enjoy ourselves as well as we can with so much suffering round us.

We hear the Soldiers Relief Society is broken up in New Bedford. I trust it will soon be reorganized for there is great need of stores among the sick. Bandages, lint, brandies, and all those comforts are greatly needed. we find the soldiers generally cheerful and many say they will return to the Army as soon as they are permitted.

I expect I am losing in French while I am gaining in another kind of knowledge. You must help me get back again when I come home. Do you go out rowing? Give much love to your grandfather and grandmother and to Em Cummings & family. Just say “how d’ye do to me” or send some message when you write. If you cannot write, a note for your messages are very welcome. It is raining out and everything looks so refreshed. Write to us often as you can,

Goodbye. Yours with love, — Fanny

Letter 6

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his niece, Miss Carrie Jenney. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Before Petersburg

Saturday, August 13

Dear Carrie,

I suppose when this reaches New Bedford you will be at Camp Meeting. Nevertheless here goes. for three days later “from the front.”

There is a hill about half a mile from our camp from which we get a splendid view. Think of the nicest view you ever had from a high bluff where there is an uninterrupted view for miles and you can get some idea of this place. On it is our outward station of pickets and at its foot rolls the Appomattox—the boundary of our powers. On the other side of this in a dense woods are the Rebel pickets and back of them, as far as we could see, low woody land, filled with Rebs. I was up there last night and enjoyed it hugely. Away to our left could be seen the spires of Petersburg, while just across a ravine in the same direction and two miles distant was the Rebel fort Clifton, concerning which we received the pleasant information that if the Rebs desired it, they could rout us out of our camp by its guns. On our immediate front I could hear a Rebel band playing, probably in one of the many camps concealed by the woods. Still further to the right was seen the portion of country in our own hands—Bermuda Hundred, Point of Rocks, and quarter of a mile in the rear to the left was our Fort Converse. So much for that view. ¹

Fort Darling and one other fort on the James between us and Richmond have thus far proved too much for us. They are situated on the bluffs by the side of the river and it is found impossible to elevate the guns enough to hit them. Under these circumstances Grant has begin a dodge. Get a map and you will see that the river winds something like this. [sketch] Now he is going to build a canal 30 feet deep around and back of one of these forts and thus get his gunboats between the forts and Richmond. A canal of a miles save three or four if windings beside. Now of course the Rebs are not expected to allow him to fo to work unmolested. They have redoubts in every direction over there and of course would open on him. 1200 volunteers are digging. Last night the 2nd Corps, Gen. Hancock, passed by our camp to go over there and support. The wagons and artillery were over three hours in passing. Besides this, I hear that a rebel ram came down the river yesterday and somehow or other they penned her so she would have to fight to get back by placing batteries above her. Now while I am writing, there is a fight of some kind going on over there, but what it is I don’t know. It may be the ram and it may be at the canal.

I have found out that I need stay only five weeks if I desire to get home. I may therefore reach home in time for next term. I rather hate to get back a week after term begins.

— Frank

¹ In his report of 1 July 1864, Engineer Godfrey Weitzel wrote that “for the greater part of the month [the construction construction of battery placements] have been under the charge of Col. H. L. Abbot, First Connecticut Heavy Artillery…Under his supervision a battery of 20-pounder Parrotts has been erected on the right bank of the James River about 500 yards below the right of our line, which commands the reach below Doctor Howlett’s house, and can act as a counter-battery to the rebel battery there. The signal and lookout tower…was completed early in [June]. It is on ground ninety feet above the Appomattox River, and is itself 125 feet high. From it can be seen the city of Petersburg, the Petersburg and Richmond Railroad, the rebel Fort Clifton and works, Port Walthall Junction, and the Appomattox River, and all the cleared country this side of the railroad.”

Letter 7

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his niece, Miss Carrie Jenney. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Before Petersburg

Sunday, August 14

Dear Carrie,

I have found out by sad experience since I have been out here that about one in three of the letters directed to me reached the desired destination. Your letter No. 2 before No. 1 and No. 1 had traveled far out of the track and been read by a man by mistake. Josie has written four to the Dr. of which he got only two up to date. Although I have been away nearly three weeks. I have got only two letters from you. Now I know I ought to get more than that. I have written six or seven letters to you and that you may know, one yesterday (Saturday) and one last Thursday and at the same time a note to Father. I have also written twice to Em[ily]. Now if you get this, you can tell whether all my letters have reached you or not. Whether they do or not, I don’t know and therefore never write a long one, but send a short one every other day. Some must reach New Bedford. These flies are enough to drive a man distracted. I write a word and then thrash.

When I wrote yesterday firing was going on very heavily on our right. I told you then that I thought it was Fort Darling. Since then I have found that that was a correct conjecture. The Rebs opened on the canal from four or five different points and made things hot for two hours or so. A rather curious calamity happened during the engagement. A hospital steward had his arm shattered by one of the shells. He was placed upon the amputating table and the surgeon began to operate for the purpose of cutting off his arm. While thus engaged, a shell came, killed the man on the table and took off the arm of the surgeon. They came over here to get our surgeon to take his place.

The other side of the Appomattox [River] is in the hands of the Rebels and by walking to its banks, we can frequently hear what is going on. They are having a revival over there and in the evening they can be heard singing, shouting, and praying. That seems odd, doesn’t it?

The flies are so fearfully thick that I will bring this scribble to an abrupt close. Yours up to Sunday, — Frank

Letter 8

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his niece, Miss Carrie Jenney. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Same Place

[Before Petersburg]

Tuesday Morning

August 16th 1864

My Dear Carrie,

Now for two days later. I suppose you think that down here we know of everything that is going on, but that is a decided mistake. But if you ever thought that it was a great place for reports and “canards,” you can flatter yourself that you were wise. For instance, yesterday we heard that our forces had captured Fort Darling. Of course it was a lie. But every day there is something startling. The last is that the whole army is to be transferred to the right across the James. That the 2nd Corps have gone we know for they passed here on two succeeding nights. We hear that they have had a fight. I hear also that the 9th Corps (Burnsides) is to be moved and also the 18th but it is impossible to get the real news. It is probable, however, that fighting for the present will be north of the James.

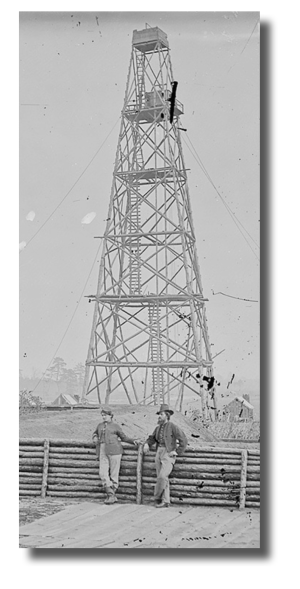

Yesterday we made a little excursion, partly to carry supplies across the Appomattox ¹ to regiments guarding Butler’s works, but if the truth were told, a great-deal-much-more-partly to see the sights and go up in a signal station. If you will look at “Frank Leslie’s” or “Harper’s Weekly” for July 16, you will see a picture of the station. ² From its top we had a magnificent view. From it we could see both Richmond and Petersburg; the roofs of the houses of the latter. About a mile from us were the Rebel pickets and behind them were their line of earthworks. We could see these distinctly and through the glass we could watch these “Johnnies” here and there on their works and behind them. Behind all this the headquarters of Gen. Beauregard were pointed out to us, while behind us were those of Gen. Butler. On the whole, the panorama was far ahead of anything I ever saw and well repaid our climbing up the giddy height.

Yesterday we made a little excursion, partly to carry supplies across the Appomattox ¹ to regiments guarding Butler’s works, but if the truth were told, a great-deal-much-more-partly to see the sights and go up in a signal station. If you will look at “Frank Leslie’s” or “Harper’s Weekly” for July 16, you will see a picture of the station. ² From its top we had a magnificent view. From it we could see both Richmond and Petersburg; the roofs of the houses of the latter. About a mile from us were the Rebel pickets and behind them were their line of earthworks. We could see these distinctly and through the glass we could watch these “Johnnies” here and there on their works and behind them. Behind all this the headquarters of Gen. Beauregard were pointed out to us, while behind us were those of Gen. Butler. On the whole, the panorama was far ahead of anything I ever saw and well repaid our climbing up the giddy height.

I will tell you more when I get home. You remember that they wouldn’t take us for less than six weeks when we started. This was longer than we wished to stay, for my own part because it took a week out of my Senior Year. Since then that “Public” makes me less desirous of getting any more deductions and I am not certain the old Betties will excuse me. On getting to Washington I found out that day they took them for five, four and even three weeks, and I met some college fellows that they took for a shorter time, so they might be back to college. Under these circumstances instead of remaining ten days in Washington, I shall stop but three and get home so as to serve five weeks instead of six. This arrangement will bring us to New Bedford on Wednesday or Tuesday, August 29th or 30th. We shall all come together.

Had a delicious rain last night. You don’t know how we appreciated it after days of burning heat. — Frank

¹ Undoubtedly Frank Brownell and Dr. Irah Chase crossed the Appomattox River on the 560 feet long pontoon bridge that was constructed at Broadway Landing for the passage of the 2nd Army Corps.

² This signal station was probably the one commonly called Butler’s Signal Tower which was located near Butler’s Headquarters at Point of Rocks. It was said to be the highest of the signal tower stations built near Petersburg.

Letter 9

This letter was written by Dr. Ira Eaton Chase (1831-1919) to his wife’s niece, Miss Carrie Jenney. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Dr. Case was married to Josephine Brownell on 1 January 1856 in New Bedford.

Near Petersburg

August 20th 1864

Station of the U. S. C. C.

Gen. Hospital 18th Army Corps

My Dear Carrie,

The letter which you have been owing me during the last year or two arrived safely at our “Headquarters” a day or two since. I was rejoiced in my distant location upon the “sacred soil” of “Old Virginia” to recognize the familiar handwriting and read the kindly message from my beloved niece, far way amid he quiet, peaceful scenes of dear New England. I have found very little leisure for epistolary correspondence aside from my “Notes” for the Bi-weekly and often-times I have only secured an opportunity for this labor after the other delegates were in bed. I have delineated in that rambling scribbling all the details of our journey—a description of our location and the incidents of interest in our field of labor and varied excursions.

I have ordered a copy of end paper containing a letter to be forwarded to 39 Spring Street so that if the mails do their duty, you will in due time receive a “report of our proceedings” and thus become well informed in regard to all our experiences. The excessive heat of our first two weeks has been mitigated by a welcome rainstorm which has nicely cooled the atmosphere and laid the enormous clouds of dust which covered all terrestrial objects. The poor soldiers in their scanty shelter tents upon the damp ground have suffered sadly from the change. The relief in one direction has proved a source of great physical discomfort. How they survive all their exposure even in a convalescent camp without any allusion to the severe ordeal of the battlefield and rifle pits is a perfect mystery to the uninitiated.

I heartily wish that every loyal citizen of the North could gaze upon their experiences and every Copperhead was forced to endure their hardships and fatigue. A happy result would certainly ensue. The former would most earnestly unite in labors of love for the relief of the Army, while the latter after [only] a brief personal experience, would be forever silenced. I wish you could be here for a little time to witness all the novel sights—wagon trains, ambulances, corrals full of horses and mules, encampments, artillery, cavalry, infantry marching in all directions, forts, embrasures, redoubts, bomb-proofs, rifle pits, Richmond, Petersburg, Rebels and all the exciting panoramas daily passing before us.

I would like also to have you hear the heavy booming of the cannon and mortars, the roll of musketry and all the varied war-like sounds which continually surrounds us. Often-times they open up all along the line and the combined roar of the artillery is real exciting. We can hardly keep quiet. We feel as though we must irresistibly rush to the scene and “join in the fray.” A few nights since the firing was of the most unusual rapidity. The reports following in quick succession as often as every second. We could scarcely count the explosions.

I have completed all the requisite arrangements for Josie and Fannie to come down and spend a day or two in visiting all the “sights” with us at the end of our term of service. We can all return to Washington together. All that is necessary to finish the matter needs afford them an opportunity of so novel an experience is a pass from the Secretary of War. I have written to them and I presume that Provost Marshal [Col. Timothy] Ingraham will easily procure all their needs. If so, they will be down Tuesday or Wednesday next. I should be titillated to see you at the same time. Hoping to see you in “propia persona,” I remain your affectionate and August Uncle

Letter 10

This letter was written by Thomas Franklin (“Frank”) Brownell to his niece, Miss Carrie Jenney. Carrie was the 17 year-old daughter of Caroline (Brownell) Jenney (1823-1855) and Benjamin Frank Taber Jenney (1821-1908) of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Before Petersburg

August 22, 1864

Dear Carrie,

Very little has occurred since I last wrote to tell you about and “our own correspondent” is at a loss with what to fill up this epistle. However, the military operations of the last week are rather interesting. You must know that there are in this army the 2nd, 5th, 9th, 18th, and 10th Corps. Now all these, I believe, were in the immediate vicinity of Petersburg just before we came. The 18th on the left, then the 9th, and then the 5th. The 2nd was reserve. The 10th had been sent across the James. That is the way the army was ten days ago. The game was very nearly the same as that which was played at the time of the explosion.

On the first place the 2nd corps was withdrawn and sent to our extreme left. They were two nights in passing here and I went out and watched them for an hour one night. After a pretended embarking for Washington, they crossed the James and as near as I can find out, got fearfully beaten over there [see Second Battle of Deep Bottom]. I have talked with a good many of them returning and that appears to be the general story. Whether it was really an attempt on Richmond or only a diversion, no one except U. S. probably knows. While the 2nd Corps were gone, the other Corps—that is, the 9th & 18th were straightened and thinned out to hold those portions of the line held previously by the 2nd. That made our line very weak and I suppose if the Rebs had known of the weakness and had the men, they could easily have broken through.

First we heard firing over on our right and reports of the battles across the James which you have no doubt read came. The second night after the 2nd Corps left, the Rebs opened on our left where as I have stated we were weak. For about three hours the firing was as heavy as any during the campaign—so the officers here said, and as for myself I never heard such a bellowing and roaring, not even in the salutes it has been my lot to hear. The “Johnnies” were feeling our strength. Then in a day or two we heard for an hour or so volleys of musket and occasionally a cannon. we were soon informed that our forces had seized the Weldon Railroad. The 5th Corps had done this. I said before they were in reserve; probably for this purpose while the diversion was being made across the James. So you see they were first fighting eleven miles to our right or north of us and then on the extreme left or south of us about six miles.

On Sunday morning, the day after the seizure, we heard them fighting again. This was yesterday. The firing began at about 3 in the morning (so I was told) and lasted till noon (so I know). It was bang! bang! bang! all day. I went out on a hill near here on the Appomattox where our pickets are and where I could see Petersburg and watched. But it was so far away that there was little to be seen except clouds of smoke. This morning I saw a “Commissioner” from there and he told me that the Rebs had attempted to get back the railroad; had made six charges with four battle lines on the fortifications the 5th Corps had erected hastily. The prisoner taken stated that “Gen. Beauregard told his men that the railroad must be regained before sundown. Everywhere the Rebs were repulsed and the “vital point” is still in our possession. If all this is true, the fighting over the James may not be without its good effect in drawing the seceshers towards Richmond.

You see that it is rather exciting here to hear the guns roaring so at all times. We had one delegate that I thought was rather scared. Almost every night we get awakened by the firing although it is never [closer] than two miles. Picket firing however is nearer.

There is an excitement about it out here that I like and if it wasn’t for [my fall] term, should stay another month. But if I should stay even a week into term time, I should feel all the time as Father does when he is away while one of his buildings is repairing. The only bad thing about it is that it is so unhealthy here. It wilted me beautifully at first and now I always have a disagreeable consciousness. There is no place on earth where a man needs a good reliable set of digestive organs more than here. It makes a man feel weak as can be and among our delegates somebody is “out of kilter” all of the time. Two men came down were sick a week and started for home. I have only two days left to serve.

The Dr. has sent for Jo[sie] and Fanny to come down here to stay one day. I sincerely hope they will not come. It is no place here in my opinion for ladies. If I ever have a wife, she shan’t come within a hundred miles of an army.

This morning I got four letters and two papers. It appears that the chap at City Point stowed away my letters; said he didn’t know where I was. Yours of the 15th and 8th (inst. before [ ]) and one from Em[ily] dated the 10th. The postal arrangements of the U. S. C. C. are decidedly bad. Don’t write after you get this. I shall be on my way home to arrive August 31st.

Miss [Dorothea] Dix ¹ visited our hospital today. Didn’t know of it till after she left. Did me lots of good.

¹ Dorothea Lynde Dix (1802-1887) was placed in charge of all female nurses in Union military hospitals. She believed women, not men, were superior caretakers. She demanded all nurses be plain-looking and at least thirty years of age. Because of her autocratic style, Dix was nicknamed “Dragon Dix,” and she often clashed with the military officials and ignored orders.