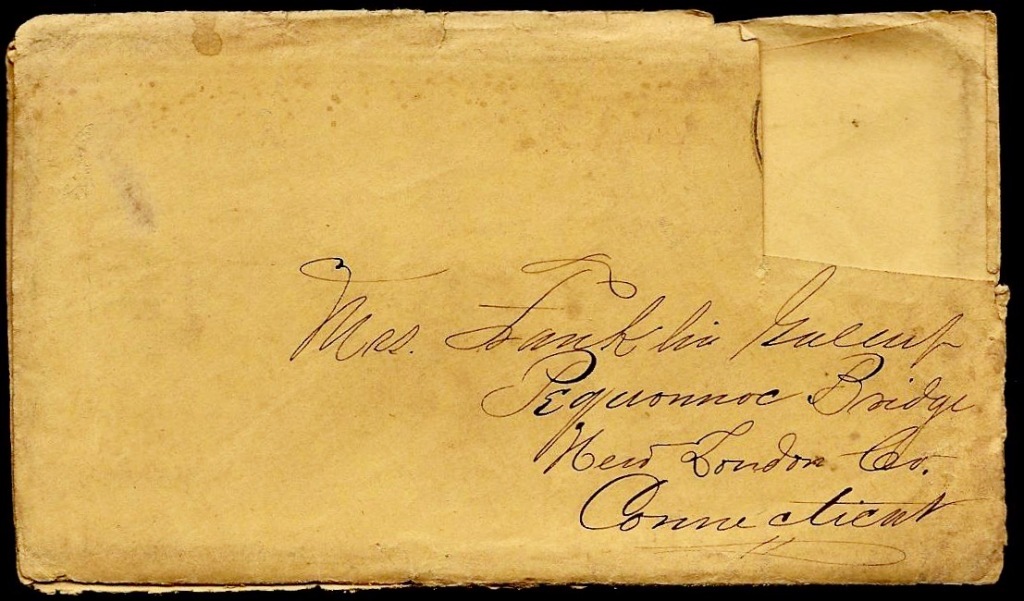

These letters were written by Frederick Gallup (1841-1922) who enlisted as a private in Co. D, 8th Connecticut Infantry in September 1861, and was promoted to Commissary Sergeant of his regiment on 30 October 1863. He mustered out of the regiment at Lynchburg, Virginia, on 12 December 1865.

Frederick (“Fred”) was the son of Franklin Gallup (1812-1899) and Hannah Burrows (1813-1843) of Pequonnoc Bridge, New London county, Connecticit. After his biological mother died when Fred was only two, his father married Sarah E. Burrows (1823-1901) to whom he wrote some of these letters. He also wrote to an older brother named Capt. Loren A. Gallup (1839-1896) who served in Co. F, 26th Connecticut Infantry.

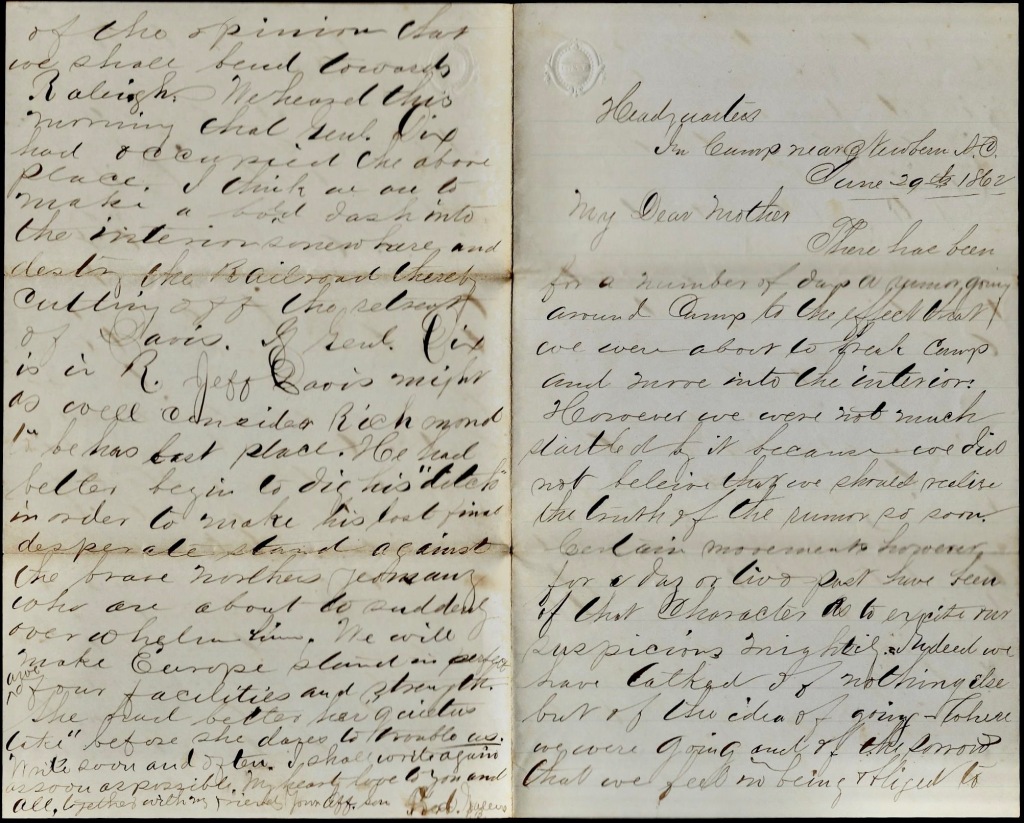

Letter 1

Headquarters

Newbern, North Carolina

June 5th 1862

Dear Mother,

Your long expected letter of May 25th has at length arrived much to the ease of my anxious mind. Every mail that came in camp I would certainly expect a letter from you but would as often get mistakened and that was last Monday. I received one the same day from Frank. Your letter as you hoped found me in the enjoyment of my usual good health, the same contentment of mind, and the same zeal and hope for the cause of freedom as ever.

“Some [soldiers] feign sickness or pretend to be sick when nothing in the world is the matter with them but babyish home sickness. We call them ‘bummers’ in the army. [They] do no duty whatever and in response to the surgeon’s call, visit the hospital every morning to get their regular ration of quinine for a month or more…”

I am glad that I am not home sick as some of the boys are in the regiment. They take no comfort themselves and are nothing but a constant bore to the respective companies. Discharges are getting to be very popular—together with furloughs. Some feign sickness or pretend to be sick when nothing in the world is the matter with them but babyish home sickness. We call them “bummers” in the army. [They] do no duty whatever and in response to the surgeon’s call, visit the hospital every morning to get their regular ration of quinine for a month or more or until they are successful in their plans and obtain a discharge or a furlough for 30 days. Some have taken so much quinine and have been so desperately homesick—young fellows—that their hair is turning gray. Poor fellows. They had better stayed at home and been cradled a while longer. They have never been the means of strength to the army except numerically, but have decidedly imposed upon the government. Their patriotism never run any deeper—yes, run deeper than their hearts right straight by them into their pockets, and just to hear the name of being connected with the army. I’ve heard them say, “Well, if I had known that it was going to be as ‘tuff’ in the army, I never would have enlisted.” Of course there are exceptions. I want to stay with my regiment if necessary even to the bitter end of the term of my enlistment.

Well, I guess this style writing isn’t very interesting. I don’t see how I struck on such a strain. I will let it go, however, ad if it isn’t agreeable, please pass it over. I don’t always write things pleasing or interesting, and you mustn’t expect me to. If I deviate from the ordinary course at times, you must not be surprised. Well, I don’t intend to write you but a short letter because I haven’t the time just now. I shall write you again soon.

Last week we were paid off. Tomorrow or next day I shall send you by Express to New London $90. In the same package will be ten dollars for Elias making $100. I trust that it will reach you in safety. Have you got that box. In it I forgot to mention of some shells that I got at Hatteras Inlet.

I believe I have written you about our camp and Newbern. I will say however that we have the nicest camp in the whole division. It is particularly noted for its cleanliness. Major Appleman has been promoted to Lt. Col. and our Captain to the Majorship.

We have splendid weather and hot don’t talk. I am still stopping with Co. G. We live like ducks—very comfortable and convenient. The Doctor has commenced giving us whiskey and quinine mixed.

Remember me to everyone, Col. and his wife, Mrs. Dolbear &c. &c. I’m coming home when the war is ended. Write me quickly. Tell me about the farm. How is Father getting along and with much love to him and you and all, I remain yours, — Fred

I will say that James Alexander of Mystic has gone home in a furlough. He says he shall go to Peq. and if he did, he would try and stop to see you. He was the one that got hurt at the reduction of Fort Macon. He is a good fellow. I hope you will see him. Your boy, — Fred

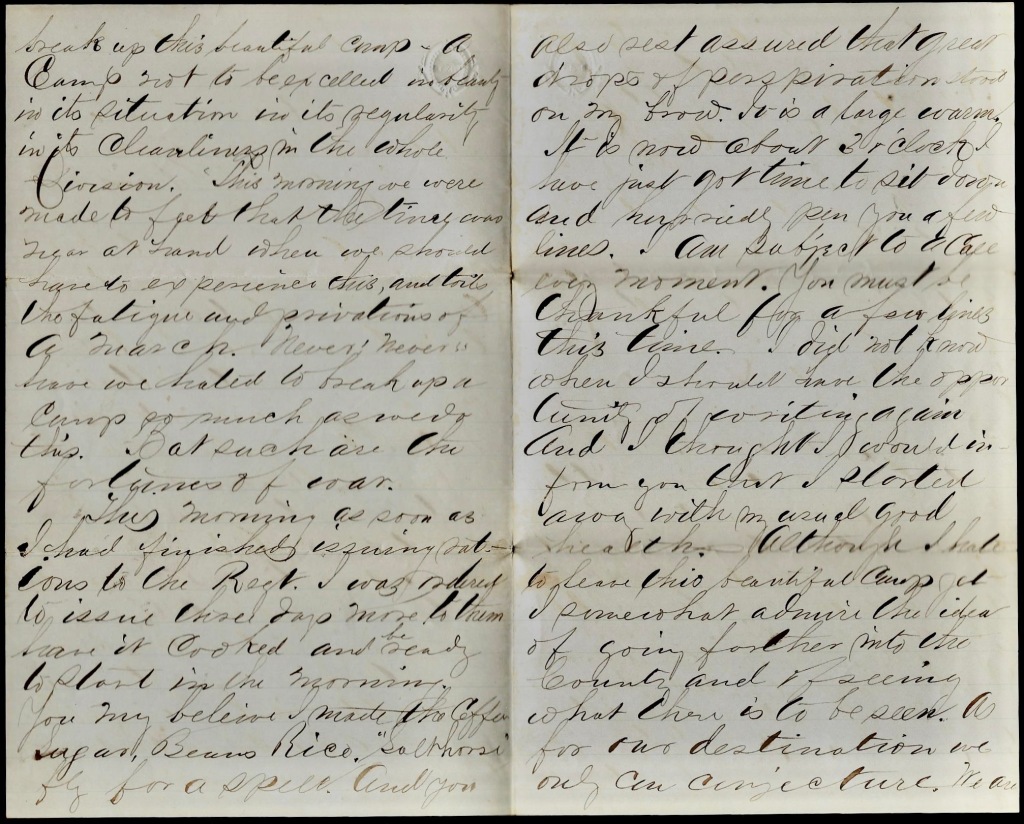

Letter 2

Headquarters

In Camp near Newbern, N. C.

June 29th 1862

My Dear Mother,

There has been for a number of days a rumor going around camp to the effect that we were about to break camp and move into the interior. However, we were not much startled by it because we did not believe that we should realize the truth of the rumor so soon. Certain movements, however, for a day or two past have been of that character as to excite our suspicions mightily. Indeed, we have talked of nothing else but of the idea of going where we were going and the sorrow that we feel in being obliged to break up this beautiful camp—a camp not to be excelled in beauty in its situation in its regularity in its cleanliness in the whole division.

This summer we were made to feel that the time was near at hand when we should have to experience this and toils, the fatigue, and privations of a march. Never, never, have we hated to break up a camp so much as we do do this. But such are the fortunes of war.

This morning as soon as I had finished issuing rations to the regiment, I was ordered to issue three days more to them, have it cooked, and be ready to start in the morning. You may believe I made the coffee, sugar, beans, “salt horse” fly for a spell. And you [can] also rest assured that great drops of perspiration stood on my brow. It is a large warm.

It is now about 3 o’clock. We just got time to sit down and hurriedly pen you a few lines. I am subject to a call every moment. You must be thankful for a few lines this time. Did not know when I should have the opportunity of writing again and I thought I would inform you that I started away with my usual good health. Although I shall have to leave this beautiful camp, yet I somewhat admire the idea of going farther into the country and of seeing what there is to be seen. As for our destination, we only can conjecture. We are of the opinion that we shall bend towards Raleigh. We heard this morning that General Dix had occupied the above place. I think we are to make a bold dash into the interior somewhere and destroy the railroad, thereby cutting off the retreat of Davis. If General Dix is in Raleigh, Jeff Davis might as well consider Richmond to be his last place. He had better begin to dig his “ditch” in order to make his last final desperate stand against the brave northern yeomen who are about to suddenly overwhelm him.

We will make Europe stand in perfect awe of our facilities and strength. She had better her quietus take before she dares to trouble us.

Write soon and often. I shall write again as soon as possible. My hearty love to you and all together with my friends. Your affectionately son, — Fred Gallup

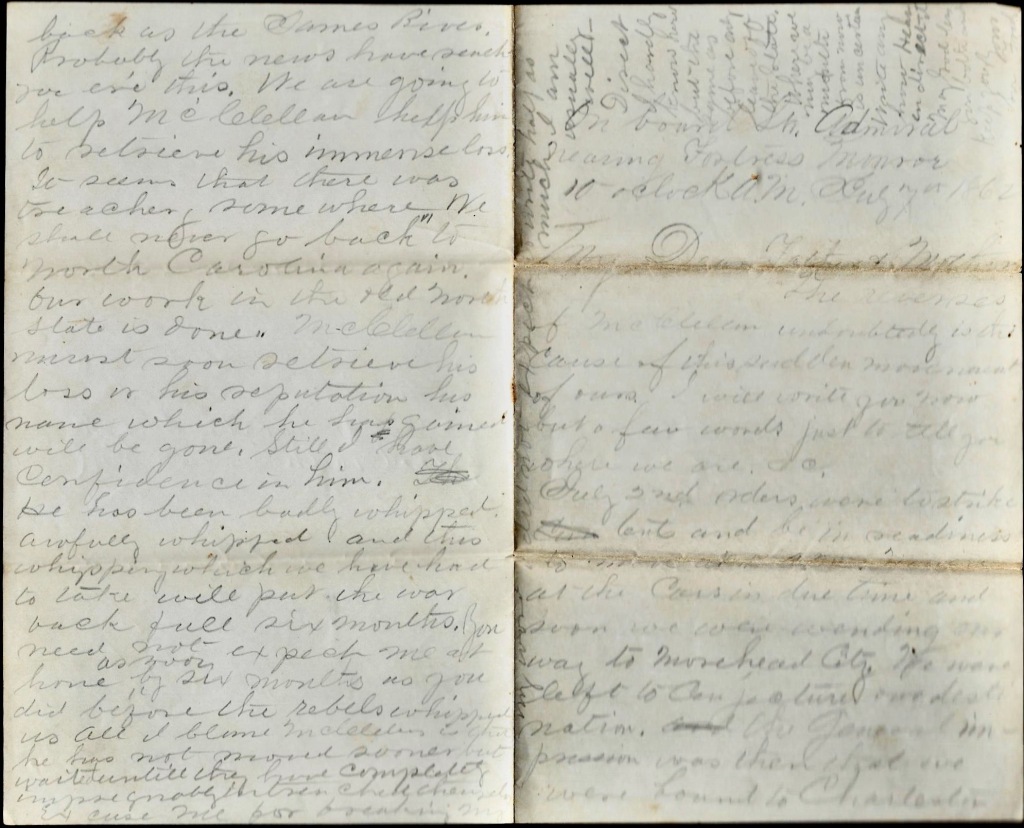

Letter 3

On Board Steamer Admiral

nearing Fortress Monroe

10 o’clock A. M., July 7th 1862

My Dear Father & Mother,

The reverses of McClellan undoubtedly is the cause of this sudden movement of ours. I will write you now but a few words just to tell you where we are &c.

July 2nd, orders were to strike tents and be in readiness to move at [ ]. We arrived at the cars due time and soon we were wending our way to Morehead City. We were left to conjecture our destination. The general impression was then that we were bound to Charleston to reinforce Hunter as we had previously learned that he had been rrepulsed.

At Morehead, we stopped over night. The next day at 10 A. M. we were marched down to the depot expecting to go on board. While we were waiting for the steamer to get in readiness, an engine alone came helter skelter down from Newbern bringing the then important and highly interesting news that the Left Wing of Mac’s Army were resting in Richmond, and countermanding our orders. Then we knew whither we were bound. We were detained in Morehead for further orders. Accordingly on the morning of the sixth, we were ordered to be in readiness to go on board the Admiral at 9 A. M. We reckoned there was something up that all was not right at Richmond. Indeed, we heard the night before we started that our army had been driven back.

The news which we so enthusiastically received was dead. Our hearts which were filled with joy and bright hopes were now, on the information of these last reports, were desponding and our former hopes seem for a time blasted. Since coming on the boat I have learned that the Left Wing of our Army was only engaged and that it was compelled to fall as far back as the James River. Probably the news have reached you ‘ere this. We are going to help McClellan—help him to retrieve his immense loss. It seems that there was treachery somewhere . We shall never go back to North Carolina again. Our work in the Old North State is done.

“McClellan must soon retrieve his loss or his reputation—his name which he has gained—will be gone. Still I have confidence in him. He has been badly whipped—awfully whipped—and this whipping which we have had to take will put the war back full six months.”

McClellan must soon retrieve his loss or his reputation—his name which he has gained—will be gone. Still I have confidence in him. He has been badly whipped—awfully whipped—and this whipping which we have had to take will put the war back full six months. You need not expect me at home as soon by six months as you did before the rebels whipped us all. I blame McClellan in that he has not moved sooner but waited until they have completely impregnably entrenched themselves.

Excuse me for breaking my word. I did not expect to write half as much. I am usually well. Direct I hardly know where but the same as before—only leave off the state. Where we will be a month from now is uncertain. Write anyhow. May God be with you both and keep you. Yours, — Fred

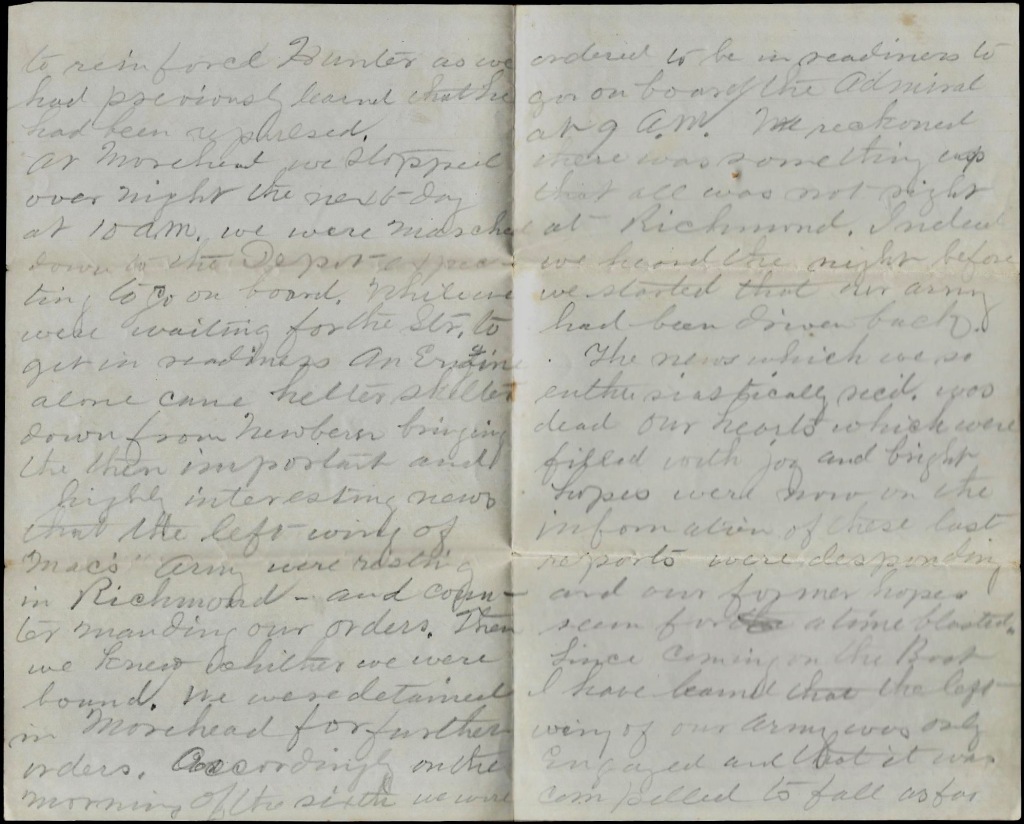

Letter 4

Office Acting Reg. Quarter Master

8th Connecticut Volunteers

near Petersburg, Va.

July 14, 1864

My dear brother [Loren],

Your communication mailed the 8th instant came to hand yesterday. Was glad to hear from you and to read from your letter so much news of general interest. Had not heard from home before since Lizzie went to W. I have written two or three times but I suppose Mother has a good deal to do. Together with those troublesome spirits about her must keep her time pretty well occupied. Expect letters daily now as Fannie and Addie have returned from school. Am glad they are to return and that father feels able to let them go. Hope that his business will be sufficiently lively this summer to meet his expectations. How is it?

Is Ben Fish catching [?] reduced so near to a science that Deacon Starr can beat all other companies combined? Frank writes me that his plan is working favorably.

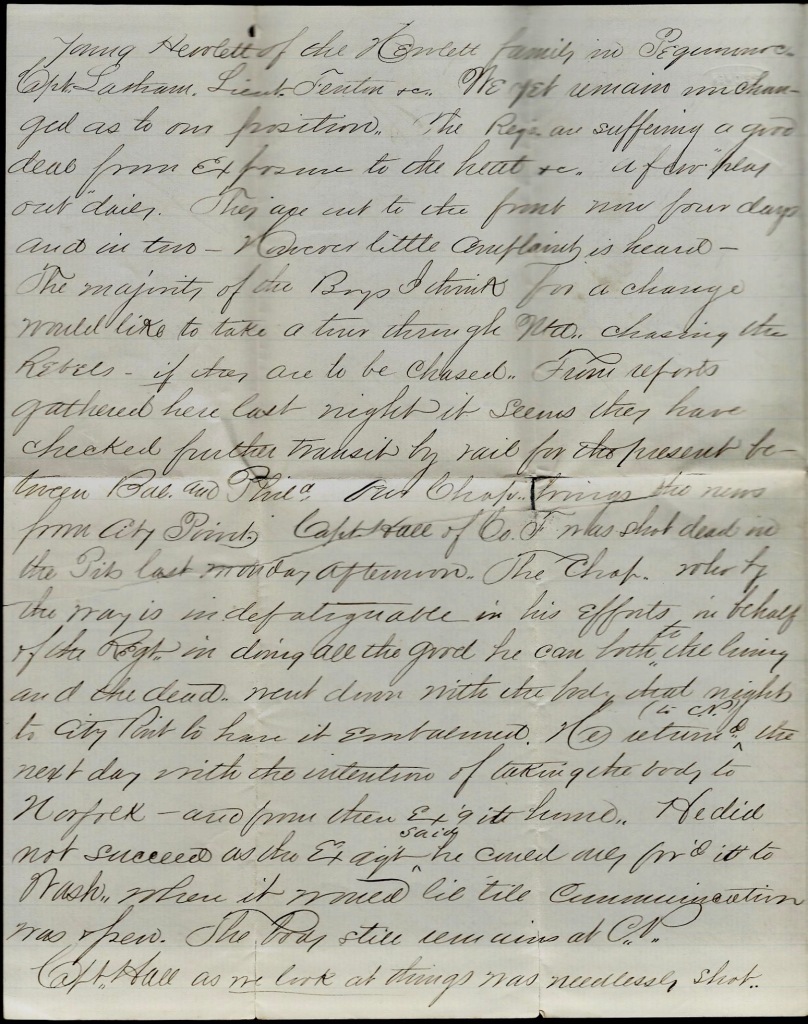

I see the 21st [Connecticut] quite often. There are but two or three men in the Regiment that I know or am acquainted with. Young Hewlett of the Hewlett family in Pequonnock. Capt. Latham, Lieut. Fenton, &c. We yet remain unchanged as to our position. The regiments are suffering a good deal from exposure to the heat, &c. A few “play out” daily. They are out to the front now four days and in two. However little complaint is heard. The majority of the boys I think for a change would like to take a tour through Maryland chasing the rebels—if they are to be chased. From reports gathered here last night, it seems they have checked further transit by rail for the present between Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Our Chaplain brings the news from City Point. Capt. [Henry C.] Hall of Co. F was shot dead in the pits last Monday afternoon. The Chaplain [Moses Smith]—who by the way is indefatigable in his efforts in behalf of the regiment in doing all the good he can both to the living and the dead—went down with the body last night to City Point to have it embalmed. He returned to City Point the next day with the intention of taking the body to Norfolk and from there expressing it home. He did not succeed as the Express Agent said he could only forward it to Washington where it would lie till communication was open. The body still remained at City Point.

Capt. Hall, as we look at things, was needlessly shot. So much the more do we deplore the circumstance. He had constructed a kind of triangular earthwork on top of the breastworks with a port hole for the purpose by way of recreation of shooting at the Rebels some 200 yards distant. The officers had been firing here through the day while one of them would look either at the left or right of the works to watch the shot [and] at the same time dodge the shots that might be fired at them by the enemy. It was in one of these instances that Capt. Hall was killed. He was watching the effects of the shots being made by one of the lieutenants. He had evidently been watched and fired at by a Rebel without success, but now two [Rebels] played the game. A Rebel fires, the Capt. dodges the bullet, hits the mark or passes over. He raises again his head just in time to receive the fatal bullet from the enemy gun who had probably a drawn sight on the spot and fired immediately on the discharge of the other’s piece. The ball, which was a sporting rifle bullet, entered at the side of his nose and passed through his head. He never spoke. He was a good officer. We feel his loss.

Col. [John E.] Ward has taken command of the regiment.

I thank you kindly for your efforts in my behalf. It seems it would be acme of my aspirations in military to be quartermaster of some regiment. I think I have a sufficient insight into the business to carry me through.

Was the Governor to send you to the Army of the Potomac? Why did you not accept? What were to be your duties?

The weather here is hot. Have had no rain to speak of for six weeks and everything is hot. We have had for two or three afternoons back decided indications of rain—big black clouds came rolling up over the sky, loud thunder reverberating through the air, forked lightning playing upon the black shifting mass and—more wind than rain. A few refreshing drops made us hope for more but the hypocritical clouds wind off leaving us to hope again.

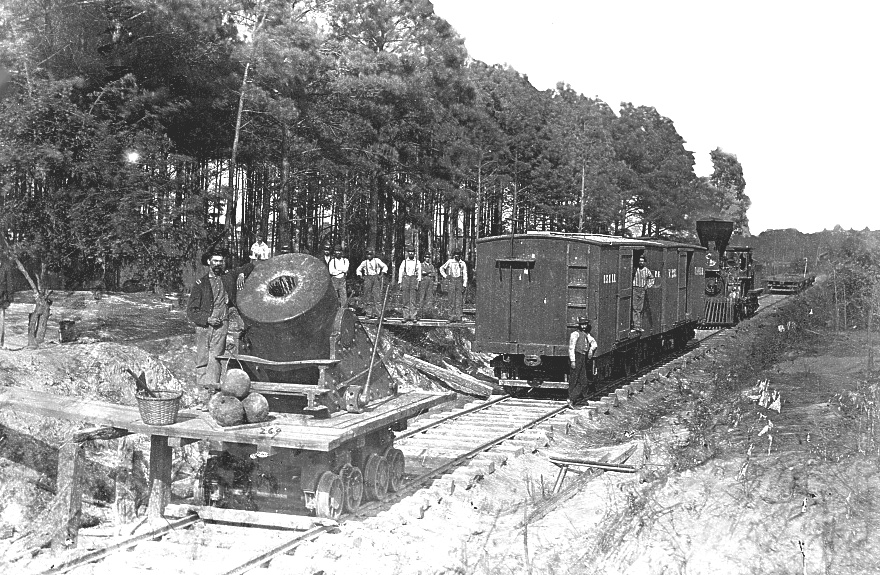

The cars are running continually from City Point here which is a great relief to the poor mules. They are not allowed to whistle—only to ring the bell.

Day before yesterday, an experiment, three shells from a 13 inch mortar was turned into or towards the city from off of a platform car. The third shot broke the frame. They are now constructing a heavier one.

We are expecting to hear of a great battle being fought or the enemy gobbled in Maryland. I hope the people North are not growing impatient. Vicksburg was not taken in a month. I am in good health. My love to you. God bless you.

Your affectionate brother, — Fred

So Albert and Thomas is now Commissary Sergt. I am now Quartermaster Sergt. Please direct your letters accordingly (via Fort Monroe, Va.) — Fred

P. S. I don’t know when this will reach you. Reports of terrible times up around Washington. My thanks for your papers—especially the Baltimore. We get now New York papers. — Fred

Letter 5

Camp 8th C. V. V. I.

In the Field, Va.

January 29, 1865

My Dear Brother [Loren],

I arrived safely in camp Friday morning the 27th instant—my birthday by the way; perhaps you remembered it. It was a cold, bitter morning and I walked to camp facing a nor-western.

The quartermaster sent my horse down Thursday night but by reason of delay at Baltimore, the boat did not arrive in due time. I arrived in Baltimore Tuesday night 1 P. M. Wednesday P. M. took the boat for Fort Monroe 3 o’clock. By the way, it being the first boat since Sunday that had left the city on account of the river being frozen. We were till 11 P. M. smashing through the ice causing the delay above mentioned. The boat was a perfect jam. General Warren went down on the boat. I heard it reported that he was to take command of our department. I hardly credit it.

I found matters remaining unchanged in some respects—in other respects changed I hope for the better. I find a good religious interest manifested among some of the members of the band. A concern for their salvation. I was somewhat surprised. Whether it is other men’s labor and we are to reap the harvest, or the immediate results of the Pastor’s labors, we don’t know. It matters not. We are satisfied to know that it is God’s work and hope and pray that He will give us a rich harvest of souls. We have a nice chapel tent and are waiting for the return of our chaplain.

The boys attend meeting at the Christian Commission. I should attend tonight were it not that I have a bad cold on my lungs taken by sleeping on the cabin floor. Am very hoarse. Aside from this, my health is good.

Perhaps you have seen an account in the papers of three rebel monitors coming down from Ruchmond on the 24th, the crew bound by an oath to go to City Point or die in the attempt—Capt. Semmes commander. How one of them was blown up in trying to pass our obstructions; the other two getting aground and barely escaping up the river. It was a daring thing and if they had succeeded in passing the obstructions, the tables I fear would have been turned on us. We had but one gunboat in the river. The rebels, it is reported, were massed for a charge. Created I understand quite a sensation here. Some 200 pounder shells came over into our camp.

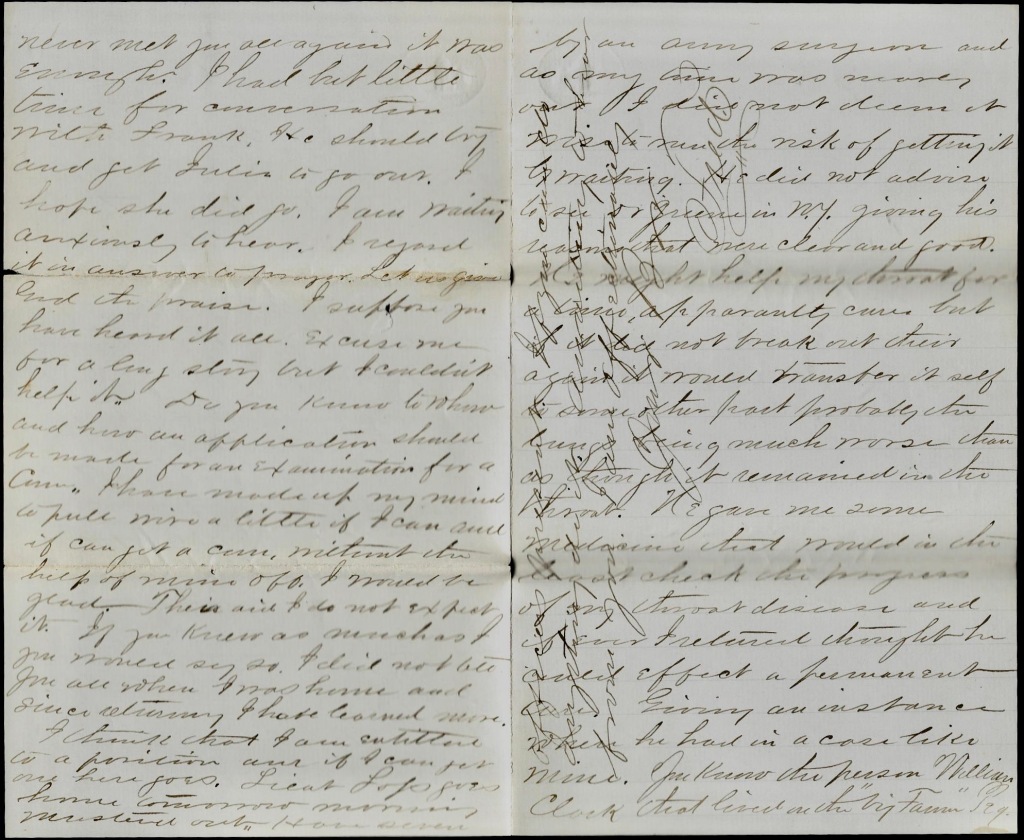

I received your note you wrote me when home. In answer to your question why I could not get my furlough extended, is because Dr. Bowen declined to do it because he thought it would be impossible giving instances where he had failed to do a like favor for a sick man. The certificate must be approved by an army surgeon and as my time was nearly out, I did not deem it wise to run the risk of getting it by waiting. He did not advise to see Dr. Greene in New York giving his reasons that were clear and good. It might help my throat for a time apparently cure but if it did not break out there again, it would transfer itself to some other part, probably the lungs, being much worse than as though it remained in the throat. He gave me some medicine that would in the least check the progress of my throat disease and fever. I returned thought he could affect a permanent cure. Giving an instance when he had a case like mine. You know the person—William Clock that lived on the “big farm” Peq.

A rainy day indeed, my departure from home. It was sad to part—the hardest that I ever had. I wonder if you have heard—I will tell anyhow. Frank came out in the morning and brought my chest. Staid a little while and was going home. Mother had not seen him. I felt awfully. I went to the sitting room and asked Mother to let me ask him in. She could not. I urged him to sit down and stay. Succeeded. Got up to go again, put on his coat, and awful moment. I went in again to see Mother. I asked again, asked to let me take the baby out. I caught a sign that she wanted to say yes but dare not. I accepted it at once and not heeding Mother’s dissenting voice, I called him in. It was a glad hour to me. They met in each other’s arms. Low words followed and tears. The overcoat was taken and Frank staid and went down with me. The parting came. I shall never forget it. [ ] was seeing to the horses & Mother were the first to part. Words and tears flowed apace and I trust there was forgiveness then. When I bid goodbye, I asked her if it was all over and told her that i had hoped while home to see the matter settled. She said it was and that she had invited them there. Oh! I cannot describe to say the feelings of my heart & felt that there was a bog load dropped from off my heart. Mingled tears of joy and gladness followed. And I thought if I never met you all again, it was enough. I had but little time for conversation with Frank. He should try and get Julia to go out. I hope she did go. I am waiting anxiously to hear.

I regard it in answer to prayer. Let us give God the praise. I suppose you have heard it all. Excuse me fora long story but I couldn’t help it.

Do you know to whom and how an application should be made for an examination for a commission? I have made up my mind to pull wire a little if I can and if I can get a commission without the help of mine officers, I would be glad. Their aid I do not expect it. If you knew as much as I, you would say so. I did not tell you all when I was home and since returning, I hope learned more. I think that I am entitled to a position and if I can get one here goes. Lieut. Loss goes home tomorrow morning mustered out. Have seven officers present. If you can do anything, do it. Awaiting to hear from you. I am affectionately your brother, — Fred