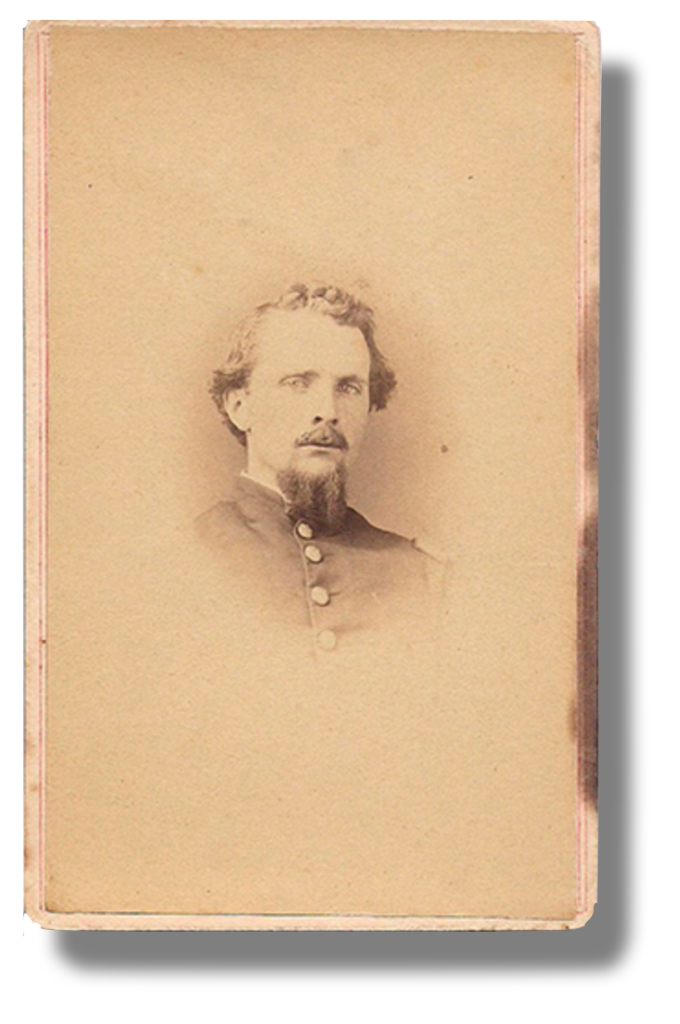

This letter was penned by Captain George S. Ringland (1834-1923), the son of James and Sarah (Stockdale) Ringland, who enlisted at age 27 as the 1st Lieutenant of Co. A, 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. In August 1862, Ringland was promoted to Captain of his company. He mustered out of the regiment on 3 October 1864—just days before this letter was written to his comrade in arms, John Jacob Barclay (1832-1908) who practiced law in Fort Dodge, Iowa, before the Civil War and was credited, with three others—including Ringland—for helping to raise the cavalry company at Dubuque which became Co. A of the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. John served from August 1861 to September 1864 (3 years and one month), rising from 1st Sergeant to 2nd Lieutenant. He was badly wounded in his left side (carrying the bullet the remainder of his life) during the fight at Ream Station, Virginia, and was a prisoner of war from 29 June 1864 to 15 September 1864, after which he was mustered out of the service as a disabled veteran.

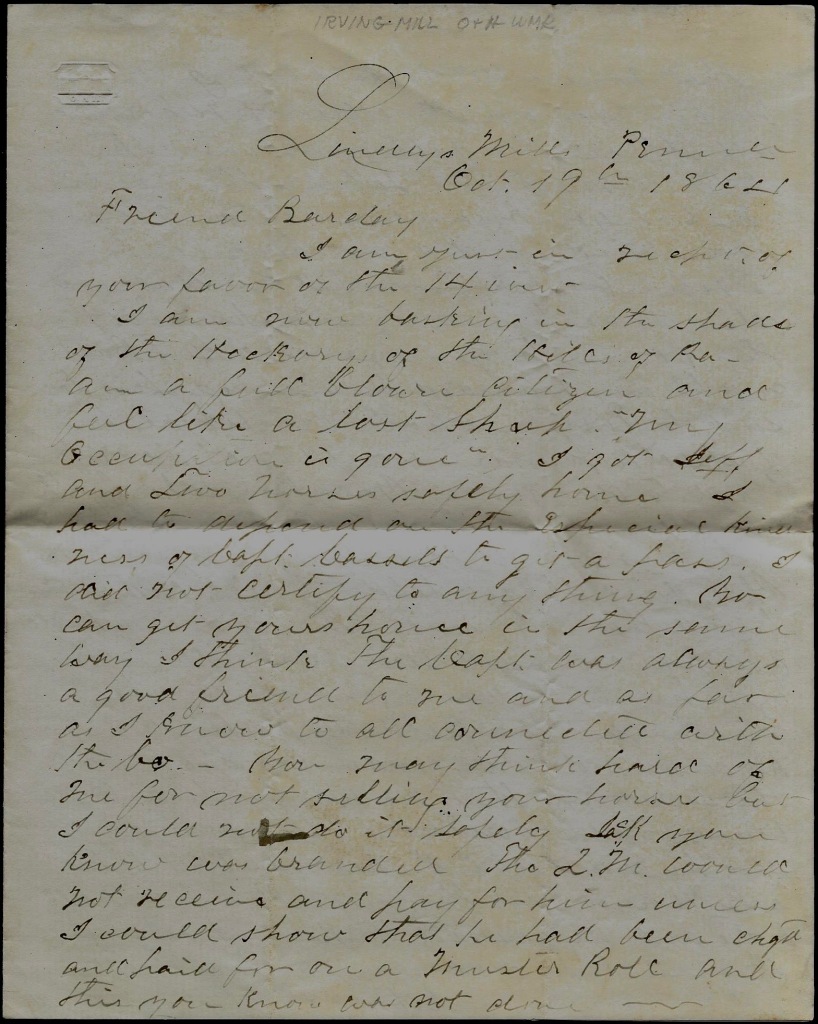

Transcription

Lindly’s Mills, [Potter county] Pennsylvania

October 19, 1864

Friend Barclay,

I am jus in receipt of your favor of the 14th inst. I am now basking in the shade of the Hickories of the hills of Pennsylvania. Am a full-blown citizen and feel like a lost sheep. My occupation is gone. I got Jeff and two horses safely home. I had to depend on the special kindness of Capt. [John] Cassels to get a pass. I did not certify to anything. You can get your horse in the same way, I think. The Captain was always a good friend to me and as far as I know to all connected with the company. You may think hard of me for not selling your horse but I could not do it safely. Jack, you know, was branded. The quartermaster would not receive any pay for him unless I could show that he had been charged and paid for on a muster roll and this you know was not done.

That miserable, deceitful, Jim Mahon got up the idea of reporting all officers for selling horses. This deterred me from taking this course. Mahon, you know, lived in a “glass house” and it did not become him to report others for what he had so often done himself. Mahon took this course to gain favor of General Butler and he was rewarded by having his company sent to Eastern shore, Va., where his dastardly person would not be exposed to danger.

Your brother, who by the way I was glad to meet in Baltimore, spoke of the war yarns that [Lt. Col. George] Stetzel spun in Philadelphia. Stetzel left the regiment without a friend that I knew of. 1 The fight in which you was wounded completely demoralized him. He was never under fire after he left that field. He pretended that he could not serve under Col. [Samuel P.] Spear but the secret was that he was at heart a consummate coward. After you were shot, he came up to the regiment bawling like a bull and told the men that they had broke and had disgraced the regiment. I resented the insult and explained that we were all in confusion before the Rebs charged on us. I got 150 men in line. Col. Spear said we could take a Reb battery that was playing on us. Stetzel turned the command of the regiment over to me—or rather let me command until Capt. Mitchell came up when he took command. Then Stetzel did not talk about breaking but remained back until we were ordered back before making the charge.

We had a fight at Ream’s Station on the 25th of August that was desperate. Harry Tuilmen was killed on that occasion as you have already learned. I would have called to see you if I had not been encumbered with my Darkie & horses. We would have a long talk together. I am not sure what I will do yet. I still think that our Richmond project would pay if Gen. Grant would only let us in but as it is, we will have to stand back for a few days.

I think some of spending the winter at Pittsburgh, but if I don’t, I will go West. I will not lay around home long. I must get ready for a [ ].

I have not received all your Philadelphia letters yet but I hope to soon. I suppose you concluded that I was very anxious to have you dead. It is still a mystery to me to know ow you got South. Will you remain at home his winter? If I go West I want you out there to help me wake up the natives.

I nearly got to deliver you an especial message from Eliza Clark who is stopping at [ ] Logan in Pittsburgh. She wants you to be sure and call on them the first time you arrive in the city. They live on Bluff Street near the lock on the Monongahela River. Call. They will use you tip top. Write soon. Your friend, — G. S. Ringland

Ain’t this a gay letter?

1 Lt. Colonel George Stetzel was court-martialed in September 1864 for “contempt and disrespect toward his commanding officer.”