This splendid letter was penned by Eugene Atwater (1842-1878), the son of master mason Henry Atwater (1815-1865) and Catherine Fenn (1817-1863) of Plymouth, Litchfield county, Connecticut.

Early in life, Eugene (or “Gene”) possessed “strong literary tastes and just prior to the Civil War attracted considerable reputation as a public lecture, his principle lecture being a carefully prepared dissertation upon the life and times of, and writings of S. T. Coleridge. While in the service he contributed a series of articles, illustrations, and descriptions of army life which was highly praised in the Waterbury American.

Eugene enlisted on 23 October 1861 as a private in the 1st Connecticut Light Artillery. Sometime between the Battle of Grimball’s Landing in mid-July 1863, and the date of this letter in September 1863, Eugene transferred to the 6th Connecticut Infantry where he worked his way up from sergeant to Captain of Co. D prior to his discharge in August 1865. He received his promotion to captain following the attack on Fort Fisher “for gallant and meritorious conduct.” Among the battles and skirmishes that Gene claimed participation were Pocotaligo, S. C., May 29, 1862; St. John’s Bluff, Fla., October 5, 1862; Grimball’s Landing onJames Island, July 16, 1863; John’s Island, Feb. 11, 1864; Chester Station, Va., May 9 and 10, 1864; Prochis Creek, May 14, 15, and 16, 1864; Wavebottom Church, Va., June 16, 1864; Deep Bottom. Va., July 26, 1864; Four Mile Creek, August 14, 1864; before Petersburg, Sept. 1864; Chapin’s Farm, Oct. 7, 1864; Darbytown Road, Oct. 13 and 28, 1864; Fort Fisher, N. C., Jan. 15, 1865; Wilmington, N. C., Feb. 22, 1865.

After the war, in 1869, Gene married Alice Hitchcock and the couple had three children. But Gene did not live long. He contracted tuberculosis and passed away in 1878 at the age of 36, his body withering away to only 60 pounds.

Transcription

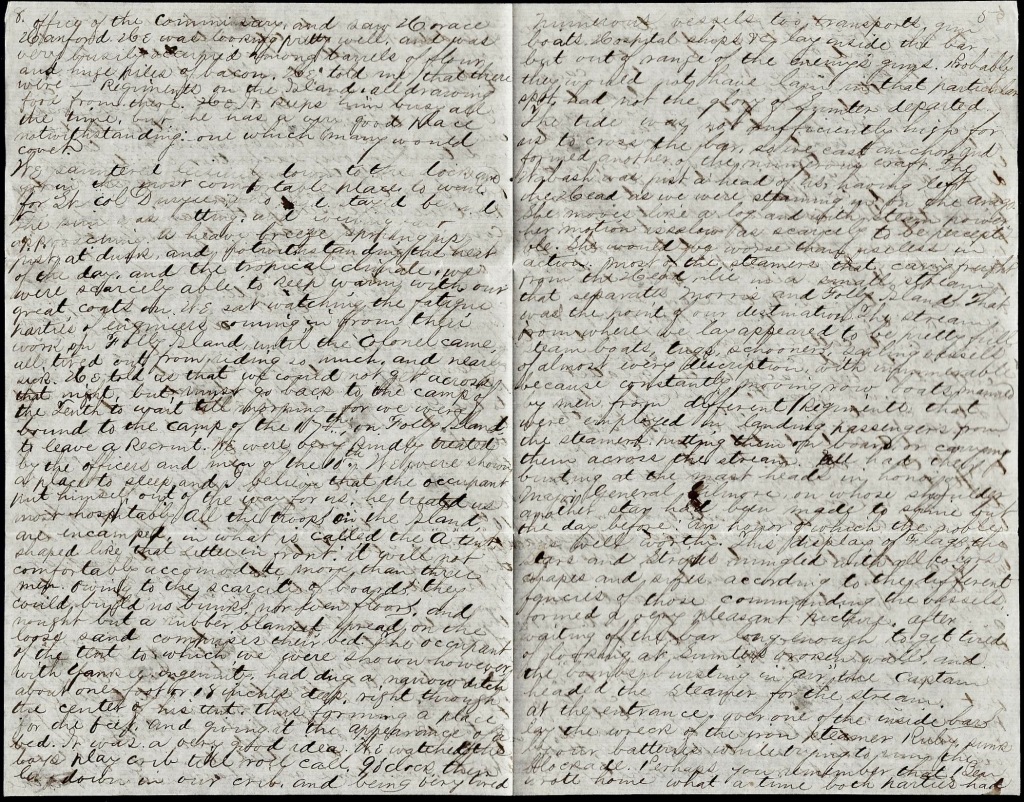

Camp of the Sixth Regiment Conn. Vols.

Hilton Head, South Carolina

September 28, 1863

Dear Mother,

Having now a little time for myself, I will improve it by letting you know how I prosper in the Land of Dixie. I informed you in my previous letter which may have been too long for your patient perusal of my movements up to the time of my arrival at Hilton Head. Our party consisted of Lt. Col. [Redfield] Duryée, Sergt. [Gottlieb] Hildebrand, Andy, and myself, and twenty recruits for the different Connecticut regiments in this Department who had to be turned over to their separate commands. The 7th and 10th Connecticut lay on Morris Island and it was necessary that the Col. [Duryée] should deliver the men in person.

Arriving at the headquarters, we stayed there long enough to get supper which we eat in the camp of the Sixth. The men for that regiment were to be left behind on the trip but I, thinking it a good chance to get a sight at active operations, begged permission to go which was readily granted. Borrowing Andy’s overcoat and with half ration of bread in a borrowed haversack, I started off and embarked on board the U. S. Steamer Monohansett. The government owns or charters many small steamboats which formerly ran to different places in the Northern states. A constant supply of them is kept here and are used for carrying mails, baggage, freight, officers, and men to and fro, different points in this Department.

The headquarters of this, the Department of the South, are here at Hilton Head but the headquarters of the Field are at Morris Island. Communication of course is constantly kept up between all points—Beaufort, Fort Pulaski, Fernandina, &c.

The steamer Monohansett is about the same size of the Ansonia and much like it as boats of that class do not materially differ. She formerly ran from New Bedford, Mass., and proved to be a fast little craft, her officers very kind and accommodating. I was placed where I could see any shirk that wanted to get away. We did not leave this dock until 9 P.M.; then dropped off into the stream and cast anchor to wait till morning that we might not have to wait off Charleston for the tide. I slept on the floor all in a heap and not very well so was up early in the morning in time to see them weigh anchor and start.

Nothing of importance occurred on the voyage. We were nearly out of sight of land and the wind was dead ahead, rolling the sea considerably. The boats generally make a six or seven hours run between the two islands and we calculated to get to the place of our destination at about noon. About ten we spied Folly Island where our regiment lay last summer and from which the assault was made that resulted in the capture of the upper part of Morris Island with the Rebel works thereon. Quite a fleet lay in Stono inlet and the shore along the whole length of the island was covered with tents. By a great mistake I had left the Colonel’s glass behind so could not be favored with a view at a distance.

On the upper end of the island was seen a tall lookout looming up like a steeple above all the trees. This is a framework built around a tall tree and continued some ways above the top with a stairway and platforms one above the other so that one standing on them can see farther as he goes higher. The enemy’s works and fortifications in Charleston Harbor and vicinity must be very plainly seen from its top.

The Sixth moved on Folly Island last April and encamped on the shore about mid-way between the two creeks on either end that form the island. You will see on the map how the land lies and where an attack must be made to be effective. Work could be done only in the night time and then only silently, as nought but a narrow but swift-flowing stream separated our working parties from the rebels who were strongly fortified or with batteries and rifle pits and would stir at the slightest noise. Our regiment could make no fires for fear the Rebs would see them and shell. So everything had to be cooped and carried a distance of two or three miles. They would go up and work five nights shoveling as hard as they could, not being allowed to speak a loud word nor by any means to strike a shovel, then go back and rest five days. The timber for the lookout was cut in the centre of the island and carried for miles on the men’s backs. Everything had to be done with the utmost secrecy and batteries were built under the noses of the Rebs when they were unconscious.

Our steamer had now arrived so near that without the aid of a glass we could see that famous sand bar called Morris Island all covered with tents. Now and then could be seen in the air little tiny balls of smoke that, growing a little larger, looked like white balloons floating in the air from which some skillful aeronaut might be making a reconnoissance and calmly looking down upon the combatants below. These wreaths of smoke were caused by the bursting of shells thrown from some of the many batteries—either Federal or Rebel, we could not tell which.

Steaming on, we soon saw the ragged walls of Sumter, standing out in bold relief—an island of itself, its face towards Wagner entirely demolished, the broken fragments still being at its base, a part having fallen into the sea. I was surprised to find it so large for you cannot judge much from a paper Fort. Over the point of Morris Island could be distinctly seen with the naked eye. The Moultrie House, Moultreville, and the Fort with [Rebel] flag flying. I could see no flag on Sumter.

Regularly, at intervals of about two minutes, smoke could be seen issuing from one of the ports of Moultrie; then watching carefully the wreath of smoke could be seen just over where we supposed Fort Wagner was situated and shortly after we could hear two reports. The enemy were keeping up a slow but constant fire of shell to prevent our fatigue parties from working. We could see the flash of Moultrie’s guns and could easily distinguish which shot came from Battery Beauregard and those on James Island. At one time as we passed along before the crossing of the bar, I got in range and distinctly saw the buildings of the doomed city. The [USS] New Ironsides with her heavy frame and grim looking port holes and the little monitors scarcely discernible lay off the harbor, silent spectators of the scene.

Numerous vessels too—transport gunboats, hospital ships &c., lay inside the bar but out of range of the enemy’s guns. Probably they would not have lain in that particular spot had not the glory of Sumter departed. The tide was not sufficiently high for us to cross the bar so we cast anchor and formed another of the numerous craft. The Wabash was just ahead of us, having left the Head [Hilton Head] as we were steaming in on the Arago. She moves like a log and with steam power her motion is so low as scarcely to be perceptible. She would be worse than useless in action. Most of the steamers that carry freight from the Head lie in a small stream that separates Morris and Folly Islands that was the point of our destination.

The stream from where we lay appeared to be pretty full of steamboats, tugs, schooners, sailing vessels of almost every description. [They] were immovable because constantly moving rowboats manned by men from different regiments were employed in landing passengers from the steamers, putting them on board, or carrying them across the stream. All had the bunting at the mast head in honor of Major General [Adams Q.] Gillmore on whose shoulder another star had been made to shine but the day before—an honor of which the noble was well worthy. This display of flags, the Stars and Stripes, mingled with all colors, shapes, and sizes, according to the different fancies of those commanding the vessels formed a very pleasant picture.

After waiting off the bar long enough to get tired of looking at Sumter’s broken walls, and the bombs bursting in air, the captain headed the steamer for the stream. At the entrance over one of the inside bars lay the wreck of the iron steamer Ruby sunk by our batteries whilst trying to run the blockade. Perhaps you remember that I wrote home what a time both parties had upon hunting her for plunder. How a boat’s crew from ether side met on her one night and our boys drove the rebs away. Many times was she the cause of our batteries being shelled and many a good rifle did our boys get from her.

We found the stream filled with vessels waiting, sailing, or [ ] from the Quartermaster. We cast anchor as the docks are not yet finished and the officers and civilians were let ashore in boats. The Colonel [Duryée] went to make preparations, secure transportation, &c., while we were left behind to wait until two o’clock. There was plenty of food for the eyes. It was all new to us though very monotonous to those on shore. Every kind of munitions of war, forage &c., horses and cattle, men—black and white, in all kinds and colors of dress were scattered on the beach in the greatest confusion while on Folly Island fatigue parties would be seen working in the sand.

At two o’clock or after, as I said before, we landed and started for the camp of the 7th Connecticut. The sun came right down on our backs although the day was not one of the warmest while the sand, ankle deep, made walking none of the easiest. However, I had no knapsack while all the others had. So I got along quite easily.

Morris Island is nothing more nor less than a huge sand bar as far as I could see. Not a tree interrupts the unbroken surface of sand although on the side towards Folly Island some grass and low bushes grow. The trees that were growing there when our forces took possession have since been cut down. In the sandy places of the island, you will occasionally see tufts of long, thick grass resembling very much what you call North ground [ ]. But the beach is splendid. When the tide is down, one could not have a better place for bathing. The sand is smooth and solid, with no breaks in it such as you see in our beach, while the waves rolling in with their white caps, makes it equal to Newport. It is grand to stand on the shore and see the breakers come tossing and tumbling over each other like dolphins in play, while the continuous roar, sounding far above the boom of the cannon, is sublime.

But we were seeking the camp of the 7th Connecticut. We had occasion to pass by the Headquarters of Maj. Gen. [Quincy Adams] Gillmore. Some of the soldiers had just before been giving him an honor salute or serenade. There was a long chariot covered with American flags drawn by six horses. In it was a band which I suppose had been playing National airs. A large eagle had also occupied a conspicuous place in the chariot but it had been presented to the General so that I did not get a chance to see it. A body of armed men on foot accompanied this as a body guard.

At last we found the camp but saw in it only one familiar face. We waited there for the papers to be turned over, then started for the camp of the 10th [Connecticut], minus ten of our party left behind. The camp of the Tenth lay just adjoining at the foot of a huge sand hill on which the Rebs had mounted guns and used as a fort. This was protected by rifle pits on which the Sixth so gallantly charged on the morning of the eleventh just before the disastrous charges of Wagner. While waiting, I wanted very much to go to the top of the mound to get a possible view of Wagner and Gregg but the way was guarded and no visitors allowed on top.

Business all finished, back we went to the dock, our party dwindled down to three. We took our time going back so I went to the Office of the Commissary and saw Horace Hanford. He was looking pretty well and was very busily occupied among barrels of flour and huge piles of bacon. He told me that there were — regiments on the Island all drawing food from there. It keeps him busy all the time but he has a very good place notwithstanding—one which many would covet.

We sauntered leisurely down to the dock and up in the most comfortable place to wait for Lt. Col. [Redfield] Duryée who had stayed behind. The sun was setting and evening fast approaching A heavy breeze sprang up just at dusk and notwithstanding the heat of the day and the tropical climate, we were scarcely able to keep warm with our great coats on. We sat watching the fatigue parties of engineers coming in from their work on Folly Island until the Colonel came, all tired out from riding so much, and nearly sick. He told us that we could not get across that night but must go back to the camp of the Tenth to wait till morning for we were bound to the camp of the 17th on Folly Island to leave a recruit. We were very kindly treated by the officers and men of the 10th. We were shown a place to sleep and I believe that the occupant put himself out of the way for us. He treated us most hospitably. All the troops on the island are encamped in what is called the “A” tent shaped like that letter in front. It will not comfortably accommodate more than three men. Owing to the scarcity of boards, they could build no bunks, nor even floors, and nought but a rubber blanket spread on the loose sand comprises their bed.

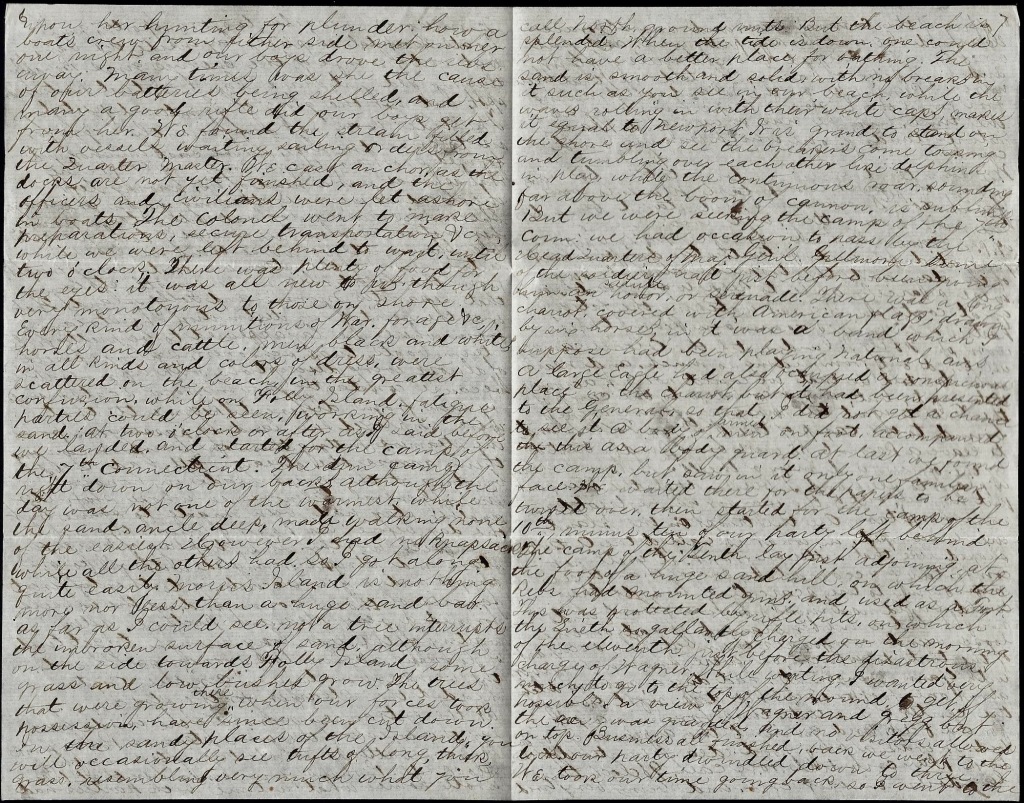

The occupant of the tent to which we were shown, however, with Yankee ingenuity, had dug a narrow ditch about one foot or 18 inches deep right through the center of the tent, thus forming a place for the feet, and giving the appearance of a bed. It was a very good idea. We watched the boys play crib [cribbage] till roll call, 9 o’clock, then lay down in our crib and being very tired, slept soundly till the rolling drum beat. Even though the enemy kept up a constant firing all night, I was not in the least disturbed. Our breakfast consisted of the soldier’s usual fare in this part of the country—hard tack and salt horse. Then the fatigue parties went out to work with the shovel and we took a fresh start for Folly Island, right glad to leave such a God forsaken spot as Morris Island. When I got up on that morning, my ears, hair, eyes and pockets and shoes were all filled with grit. Deliver me of such a place. If what I have seen is a fair specimen of the Sunny South about which romantic fools have sung, may my stay in it be short.

In a row boat we crossed over to Folly Island, tried to get a wagon but could not. Colonel got a horse and we tried to hoof it. Found out after going considerable distance that the 17th was on the shore about three miles down. Quite a pleasant prospect before us indeed. But the tide was out, the sun not very hot, and the hard beach afforded us a good foundation. We approached about 150 men drilling on the beach who, on nearer approach, proved to be negro troops though from their movements one would suppose them veterans. One squad was under command of a colored sergeant, who was putting his men through the manual of arms, drilling them by motion. He apparently understood his business and his orders were given in a full, clear tone that would have done credit to man or officer of the gold button and gilt lace order, while the men executed the movements and counted the motions with a precision equal to some older and whiter regiment. 1

The camps of the troops are situated on a high bank that rises from the beach just at high water mark, and sentries were stationed all along so that it is impossible to mass from one camp to another. We reached the camp of the 17th [Connecticut] sooner than we expected and just in time for dinner. The first fellow that I saw was George [H.] Spencer [of Newtown], the Hospital Steward. While talking with him, Henry Chatfield came out of his tent nearby. He is not very well nor has he been for some time.

Change of climate and miserable water have made many of them sick and though the regiment went out 1,000 strong and has been out but one year, it now has but few over 100 men for duty. Saw Lieut. Blum. He looks miserable. I hardly knew him. Saw George Keeler & Joe Mott but not as many of the Bridgeport boys as I expected to. Many are now at the camp of the paroled prisoners waiting to be exchanged. [Morris] Jones [of Bridgeport], that used to sell fancy goods at ___ing’s has risen to the position of 1st Sergt. [Co. K]—two more steps in the regular line of promotion, and he will have a commission.

I sat down in Hen Chatfield’s tent and had quite a talk with him. He as well as all the others, were anxious to know all the Bridgeport items. I learned for the first time than Hen had a sword shot in two and a horse killed under him. He was very brave on the battlefield of Gettysburg. 2 Colonel [William H.] Noble seemed very glad to see me. Asked about father &c. He has become very popular since Gettysburg.

Waiting for the tide to fall so that we could walk on the beach, we started back to our own camp gratified to know that our business was all settled up right and happy in the knowledge that we were homeard bound.

As we left, Col. [William H.] Noble was starting out with a part of his men who were going on picket. The tide appeared to go down very slowly and sometimes I had to dodge the waves but at one time was not going quick enough and I got my feet wet. After that I did not care but trudged right through—water or no water. Night overtook us before we arrived at our journey’s end and we were halted by the voice of the sentry challenging, “Whoes goes dar?” and friends without the countersign. “Hawt,” says the darkey, as if his mouth was full of gravel. The Colonel went to the camp of the regiment which was from North Carolina for the countersign. I wished afterwards that I had gone too, to the darkey soldier as he is in camp.

That night we spent on board the steamer Monohansett and as but few had come aboard, had a good bed in the saloon. In the morning being very anxious to get a letter to you on the return mail, borrowed some paper from the steward, and wrote the last letter to you on board the steamer waiting transportation to Hilton Head. At the time of writing, I was in the stream between the two islands—Morris and Folly. I had no ink at the time and had to use pencil. That was excusable under the circumstances. While writing, [guns] which proved to be a [salute] that were being fired in honor of General Gillmore. I afterward learned that a [ ] as had on the island that morning. Did not know it at the time but would not knowingly have missed it for considerable.

As we were about to start, the General [Gillmore] himself came on board a steamer alongside of us. He is a noble looking man and time has sat lightly on his brow. A part of his staff was with him. He went on the upper deck and stood there with folded arms watching movements about him. Not the smallest thing escaped his watchful eye.

The body of Capt. [Joseph] Woodruff of an Indiana [Illinois] regiment was brought on board. He had been killed in the trenches the night before. 3 Some heavy firing was done that night as the report of the cannon shook the windows of the boat in which we were.

Thursday morning early we arrived safe and sound in the regiment where I have been ever since, doing duty with it. Have been on guard once and fatigue twice. Expect to go on again tomorrow. My last letter would not have gone had not one of the company, going home on a furlough, taking it for me. My chum, who is going North as one of a guard for some prisonrs of war, will take this.

I miss my things very much and look for them everyday. The Arago will not be in till Monday. Ben[nett] Lewis has been appointed 1st Sergeant of Company I and will be coming down pretty soon. Perhaps he will take a small bundle for you. Need not send my tactics nor my dictionary, but that little needle book marked with my name.

I am afraid I have made this too long but my time is interrupted and writing at different times, it has not seemed so long to me. I suppose it is full of mistakes but have no time to read and correct. You will see that [ ]. I forgot myself and thought I was writing to Helen. I am perfectly well and in good spirits and want nothing more than to hear that you are all well at home.

We hear strange reports about Provost Marshal [James G.] Dunham. 4 Can you let us into the matter a little? Reading matter is very much prized by the soldiers. Indeed, did the ladies know how much they delight in books, papers and pamphlets, they would send them a great deal more. Can’t you occasionally send me a daily or weekly Standard, some weekly paper, some magazines, or the latest fills of New York papers?

Ben[jamin] Penfield is getting along finely and wishes to be remembered to you all. Ask Nell what I shall write to her about. Love to Grandmother, Aunty Ann, and all the family. Respects to all enquiring friends. Enclosed I send a copy of the New South which perhaps you would like to read. Write soon to — Gene

October 2d 1863

1 At Folly Island, South Carolina, in August 1863, the “African Brigade” commanded by Gen. Edward A. Wild consisted of the 54th Massachusetts, the 1st North Carolina Colored Volunteers (N. C. C. V.), and a small detachment of the 2nd N. C. C. V. [Source: Raising the African Brigade: Early Black Recruitment in Civil War North Carolina by Richard Reid.]

2 Henry (“Hen”) Whitney Chatfield of Bridgeport served as the assistant adjutant of the 17th Connecticut; afterwards promoted to be sergeant-major, and for gallant conduct at Chancellorsville, in rallying and re-forming the regiment, promoted to be adjutant, serving with distinguished gallantry at Gettysburg. The regiment was in the midst of that first day’s fight at Gettysburg, on the other side of the town, and west of its final battle-ground. Lieut.-Col. Fowler, commanding regiment, and Capt. Moore, were instantly killed; Lieut. Chatfield, who was beside Col. Fowler, had his knapsack and uniform riddled, and his sword––a relic of Revolutionary history—broken in splinters, yet received not a scar. Henry was killed in action at Dunn’s Lake, Fla., his death described in the following letter—1865: J. S. Walter to Benjamin Wright on Spared & Shared 9.

3 Capt. Joseph Woodruff of Co. K, 39th Illinois Volunteers died in the regimental hospital on Morris Island on 23 September 1863 a few hours after he was struck by a shell fragment while on duty in Fort Gregg. The shell was hurled into the fort from Fort Moultrie and when it burst, it killed several men and wounded Woodruff mortally in the side. Sergeant James Sanborn had the solemn duty of accompanying the remains of Capt. Woodruff to his home in Marseilles, Illinois.

4 Capt. James G. Dunham was the Provost Marshal for the 4th District located at Bridgeport. In June 1863, he posted notices in the local papers announcing the War Department’s decision to organize an invalid corps made up of officers and enlisted men who had been previously discharged for disability.